A Philosophy of Teaching

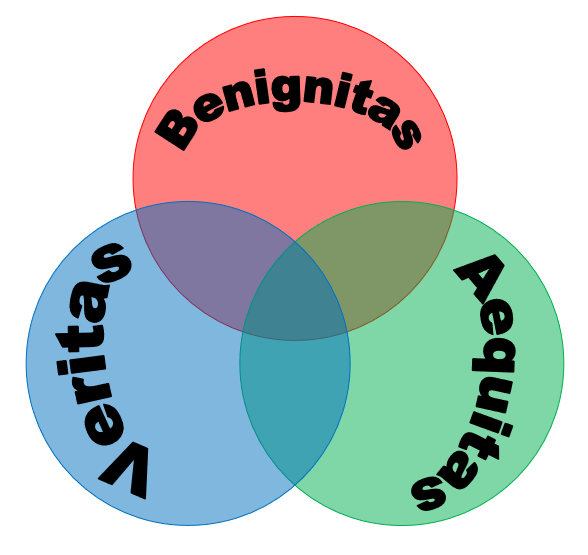

Three things seem relevant to teaching and assessing:

Three things seem relevant to teaching and assessing:

1. Benignitas. Kindness, considerateness, goodwill to students. Helping students to learn what they should learn.

2. Veritas. Truthfulness, subject correctness, integrity to the subject. Knowing the subject and what is important in it.

3. Aequitas. Fairness, equality to the social group. Fairness to students within a class and between students in different classes. Assessment standards should not differ significantly between professors or between sections of the same course. Getting a good grade should not depend on getting in a class with an “easy” instructor who grades easily to get good student grades in return. This is not fair.

The philosophy is that to be a good teacher you have to have all three qualities at once. For example, giving an A to a student who does not understand the subject is not truthful although it may be a kindness. Giving a student who begs, but has no other reason, a special chance to redo work is also kindness, but is not fair to others in the class who didn’t get that extra chance. Teaching material that is true but above the students’ level, or in a way that is too difficult for them, is being correct but not considerate of students. Grading so that any error at all results in a grade of zero, may be fair (equal to all) and show high standards, but is not considerate of students who while not perfect, still know something.

Focusing only on one aspect of teaching is unbalanced, and has manifold negative effects, on standards, on behavior, and more importantly, on morale, both of students and staff. For example, if students find their grades vary radically according to which professor, subject, or even section within a subject that they take, some will look for courses that give high grades for little work. When students who work hard for their grades see weaker students getting higher grades for less work, their morale will go down. Student attention and effort is diverted from their own learning to shopping around for easy credits. Hence it pays an institution to support course consistency, so the same student effort gives the same grade regardless of who is taking the course, when it is being taken, or how it is being taken.

A grading system of kindness, truthfulness and fairness is a much more rounded and human approach.

1. The first aspect, kindness to students, is often covered by student ratings of instructors.

2. The second aspect, of subject correctness is important because most teaching institutions are subject to accreditation review regarding their academic integrity. Since this is basically a form of peer review, it makes sense to carry out such peer review continuously internally. This can be based on the forming of teaching groups that exchange course and assessment material for “moderation”. Thus if we are in the same teaching team, while you assess my exam this time, next time I will assess yours. This moderation is not part of our promotion assessment. The result of peer checks is better exams. There is no need for the exams to be forwarded “up” to any administrative central control system. The person giving the exam submits a moderation review record to the coordinator, keeps the changed exam, and it goes no further. This is better than a “policeman” approach to quality, where some “controller” tries to oversee all activity. Teachers will carry out moderating because they like to act in groups and it gives better exams. In my experience in such a system peers almost always find errors, often major ones.

3. Finally, to increase grading fairness, it is a good idea for the grade record system to make available to teachers the grade frequencies (% number of A’s, B”s etc) for each paper. This allow them to check fairness between course sections. The teaching group should meet to resolve issues before grades are published. This does not mean making such information public. A Department Head would only receive the information for their department. A teaching team would only receive the information for their team. Problems like two people teaching sections of the same course giving widely different grade frequencies (e.g. one person giving no A’s, and another giving mainly A’s) would be resolved.

The current systems that most institutions follow tend to recognize only one or two of these concepts. Yet most would agree that all three are important aspects of teaching. If they are important, then the systems that support teaching should recognize all three, in staff assessment, training and support.

How this philosophy works is best explained by examples of teaching practices:

- Introduce yourself and get to know them. Students like to know who is teaching them. As people, not machines, we like to build relationships. It is easy to forget and start teaching your subject, but the first thing students want to know is “Who are you?” Likewise, get to know them as people. Make the class a place where “everybody knows your name”. The first step is to remember their names. I don’t have a naturally good memory, so I begin by asking them to put their names up on folded paper signs. After a few weeks, I can ask questions in class by name.

- Start with motivation. Students need motivational support to feel empowered to learn. The teaching role is as much a motivator as an information provider. In the first class, one may spend considerable time establishing why the course is relevant, how they will benefit personally, e.g. in user centered computing, I spend time convincing students that human factors are important in system design. Also go around the class and ask each of them what they want to get from this class.

- Issue the syllabus first: The course syllabus is the “agreement” between the professor and the students. It explains what the course is about, how it is assessed, what classes are when, when assignments are due and so on. The syllabus contains a lesson timetable, assessment percentages and due dates. Give students printed copies of the syllabus in the first class because it is so central. Then the students know what they have to do by when. Each class we check the syllabus and see what’s on and what’s due. Any changes, we write on their copy in class.

- Issue assignments early. It is a good idea to issue all assignments for the whole course on the first day, along with the syllabus, so those who want to plan their semester can do so. Before each assignment, go over the requirements carefully. Many students lose points because they don’t read the requirements. Tell them how you will grade it and what to watch out for. Don’t lower the standard but encourage them to rise to it.

- Be on time. It is a good thing for a class to start on time so they can finish on time. I turn up on time as a model. Being late is often ineffectualness and in a job regular lateness can result in dismissal. Hence it is good for both professor and students to be on time. Ask students to hand in assignments on time and in return, grade and hand them back on time.

- Transparent grading. For every exam and assignment, go over the answers and how the points were allocated. On multi-choice questions, students can check each right answer and add up their total. If there is an error, we fix it right away.

- Don’t “negotiate” grades. Convince students that their grade depends on their work not your attitude to them, i.e. “You grade yourselves by your efforts”. There is no sense that because the teacher like someone they will get more points.

- Negotiate the class context. Let the concept of “start on time and finish on time” be a class decision rather than my decision imposed. If a lot of people come in ten minutes late, ask the class if they would prefer to start and finish ten minutes later. When they realize rules are by mutual arrangement, students are very good. Some will come and tell me why they are late. We talk and get an understanding.

- Like and respect your students. To teach students well you have to like them and want them to do well. Respect means accepting that some students in your class may know more than you. Even if you know more than them in this topic now, in the future they may know much more than you. And even if you know this topic more, in other subjects many of them are, or will be, much better than you. It is a privilege to teach many of them.

- Open format. Students are people too and we all get bored. It helps if classes are interesting not boring. It also maintains your interest. I never know what new ideas or thoughts will come up in class because I don’t follow a rigid a format, like just reading notes. Encourage and respond to student questions, even challenges. The key here is to listen. If you, or even the book, is wrong, then don’t deny it. If unsure, decide to ponder it for a week. If you are teaching the same topic for the umpteenth time in a boring way your students will be bored. A good teacher should also be learning, as you never know when some student may give you a revelation.

- Encourage active learning. Active learning has many aspects, from student projects to asking questions in class. Students learn more by what they do than by what you say. Encourage questions in class and trying out what they learn in projects and real life. Give time in class to work on group projects and walk around to give direct feedback. Actions engage students and a student is not learning if they are not engaged. Many people don’t like active learning because they worry they will lose control, but a noisy classroom can be a productive one.

- Help students to get to know each other in class and work cooperatively. In my classes group work is encouraged but it is still an option. Students are not forced to work in groups or assigned to groups. A good student who dislikes “free riders” may choose to work alone, though naturally this means more work. Those that work in groups always choose their group. It is voluntary and if necessary, a group can “divorce”, so give procedures for that. Finally, let groups assess each other’s contribution, and take it into account in grading.

Balanced teaching is better teaching.