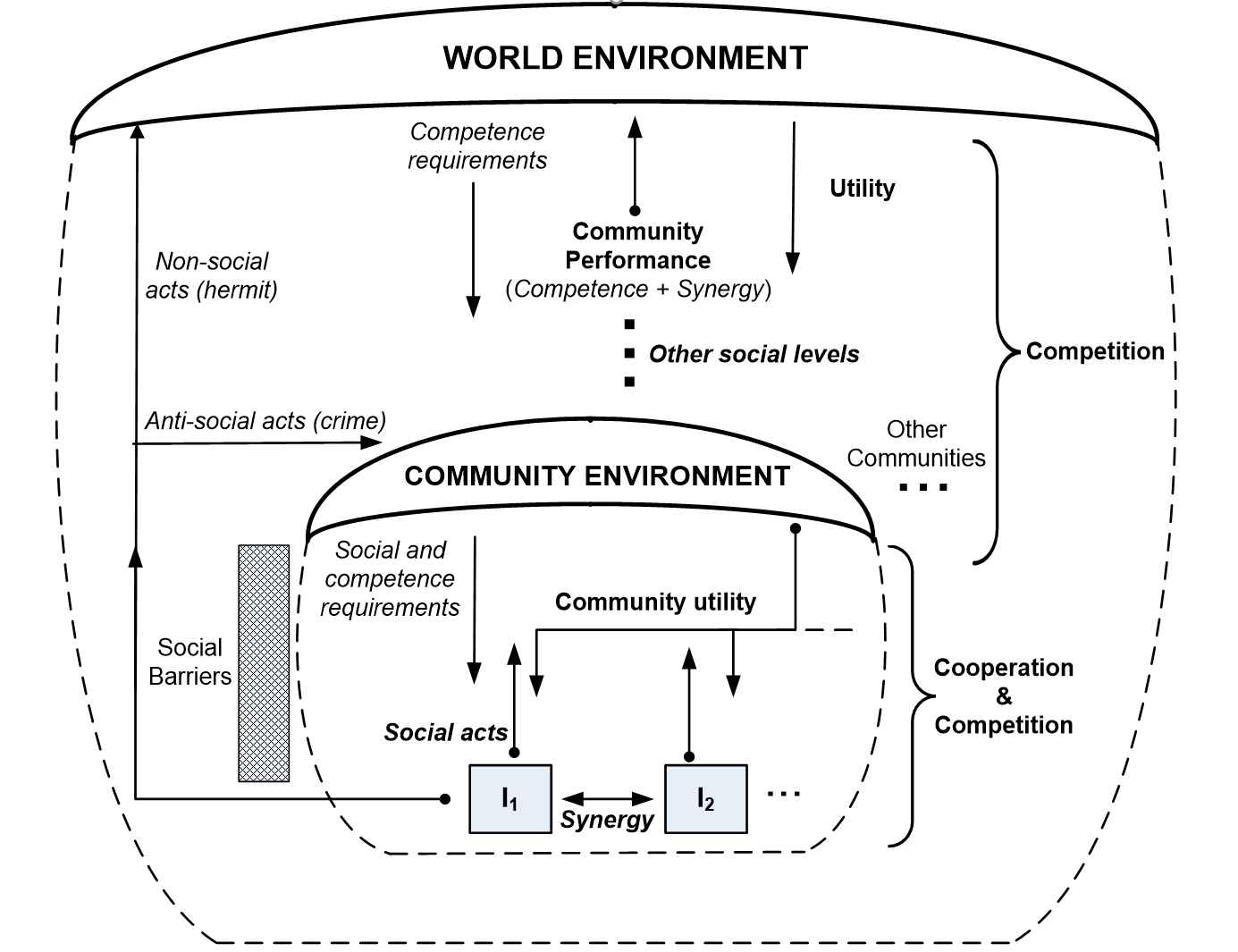

In the social environment model, people in a social system are in a social environment within the world environment (Figure 5.4). This summarizes the previous conclusion that a person in a social unit is subject to both the homo economicus and homo sociologicus world views. Since every social exists within a physical world environment, defection is always an option. While synergy requires people to work together to achieve its gains, crime is when people try to in effect “short-circuit” this path, to get immediate gains at the expense of others.

In general, we do not see environments because they are too close not too far away. Just as a fish cannot see water, or a bird the air, we as social animals tend to be social environment blind. We see the world environment that limits our actions and dispenses consequences but not the social environment that generates community benefits like roads and electricity. Yet a social system is an environment to its members because it imposes requirements on them (laws and norms) and dispenses their gains and losses (salaries and taxes). It does the latter by social tokens like money, which are exchanged for world values like food.

People in a society operate under two environments, one that rewards them for competing and one that rewards them for cooperating. It follows that the community needs to satisfy both environments. Thus social system can fail by incompetence with respect to its world environment, as when a wasteful company goes bankrupt, or from social corruption, when the group fails to create synergy or prevent crime. This approach supports Adam Smith’s view that people competing in a free market can help society only if the competition does not turn into rampant crime.

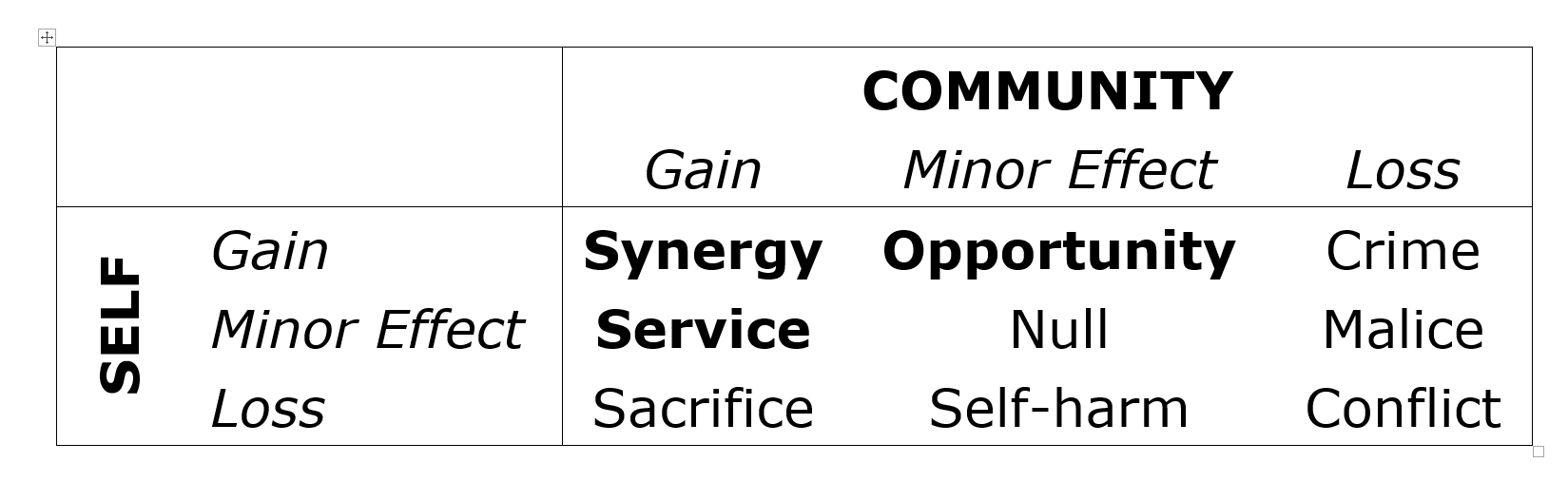

Table 5.6 shows the possibilities, depending on whether people follow Rule 1 to benefit the self, or Rule 2 to benefit the community. As can be seen, the “selfish” Rule 1 directs individuals to choose the first row, while the “good” Rule 2 directs them to choose the first column. Following Rule 1 with no regard for others leads to widespread crime that degenerates into conflict, while following Rule 2 with no regard for the self leads to sacrifice and eventually the loss of that person’s value. Thus in this model, both rules are required. This model also works in biology, as the first row is symbiosis, commensalism and predation respectively. People however have a choice, between their instincts for personal gain (Rule 1) and their social training for synergy (Rule 2).

If people only followed Rule 1, to benefit the SELF, then crime would prevail and society would collapse. If they only followed Rule 2, to benefit the COMMUNITY, we would be like ants willing to sacrifice themselves for the colony, locked in under genetically bred pharaohs. Our actual social path was a pragmatic combination of Rules 1 and 2. Taking what is positive for SELF+COMMUNITY gives opportunity, synergy and service as the prime directives of human society. In society, most people take opportunities, fair trade synergies, and give service to their fellow citizens as needed. These are not mutually exclusive, as they serve the community in war but still try to survive personally, try to get ahead without breaking laws, and help others if the cost is not too much. Yet that people naturally help others is not part of game theory. Only the social environment model makes helping others just as critical as helping yourself.

The problem facing humanity was how to combine Rule 1 and Rule 2 in a way that is feasible, i.e. doable by people. A well known solution is the utilitarian ideal of “the greatest good for the greatest number,” as popularized by Dr Spock’s sacrifice in Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan. It seems simple to prefer the greatest good but the calculation over time gets confusing? For example, is an aircraft crash that loses hundreds of lives today but causes safety changes that saves thousands of lives in the future “good”? Should governments then crash planes or sink ferries to introduce needed safety measures? The problem with the utilitarian solution is that the greatest good of millions of people over hundreds of years is not calculable by anyone, let alone a majority of people. It is valid but not feasible.

Nor does a simple AND of Rules 1 and 2 work well. It is feasible but not optimal, as people acting only to benefit both themselves and society would often not act at all. Finally, any sort of weighted trade of social utility against individual utility raises complex questions, like how much social good is my individual loss worth, or how much individual good warrants a social loss? On this logic, old people would go to war as they have less to lose, while young people would want to stay at home. What is needed is a rule combination that is simple enough for people to conceive and do. Such a solution is cognitive anchoring, fixing one rule and then applying the other (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974).

This approach suggests the following combinations:

Rule 3a: If {SU(ai) ≥ SU(aj) and IU(ai) > IU(aj)} then prefer ai to aj

In words: Choose acts that do not harm society but benefit oneself

Rule 3b: If {IU(ai) ≥ IU(aj) and SU(ai) > SU(aj)} then prefer ai to aj

In words: Choose acts that do not harm oneself but benefit society

Following Rule 3a, people seek gains that don’t harm society as defined by its laws, i.e. one competes by the rules.

Following Rule 3b, people help social others if it doesn’t harm themselves, i.e. those with “enough” give to others.

These SELF-COMMUNITY rules are easier to apply than ideals like calculating the greatest good for the greatest number, or the complex trade-off of individual vs. community gains/losses. They are valid and feasible. Yet while current society has institutionalized and benefited from the profit Rule 3a, Rule 3b remains largely ignored.