Muscle memory is a sensorimotor schema stored in the cerebellum that is activated by sensory triggers, so to know if you know how to ride a bike, you must get on one again. In contrast, midbrain memories let us re-experience past events, like whether we left the stove on. Episodic memory provides a past event timeline that can be analyzed to link cause and effect. It allows organisms to survive by emotional learning, of good or bad consequences.

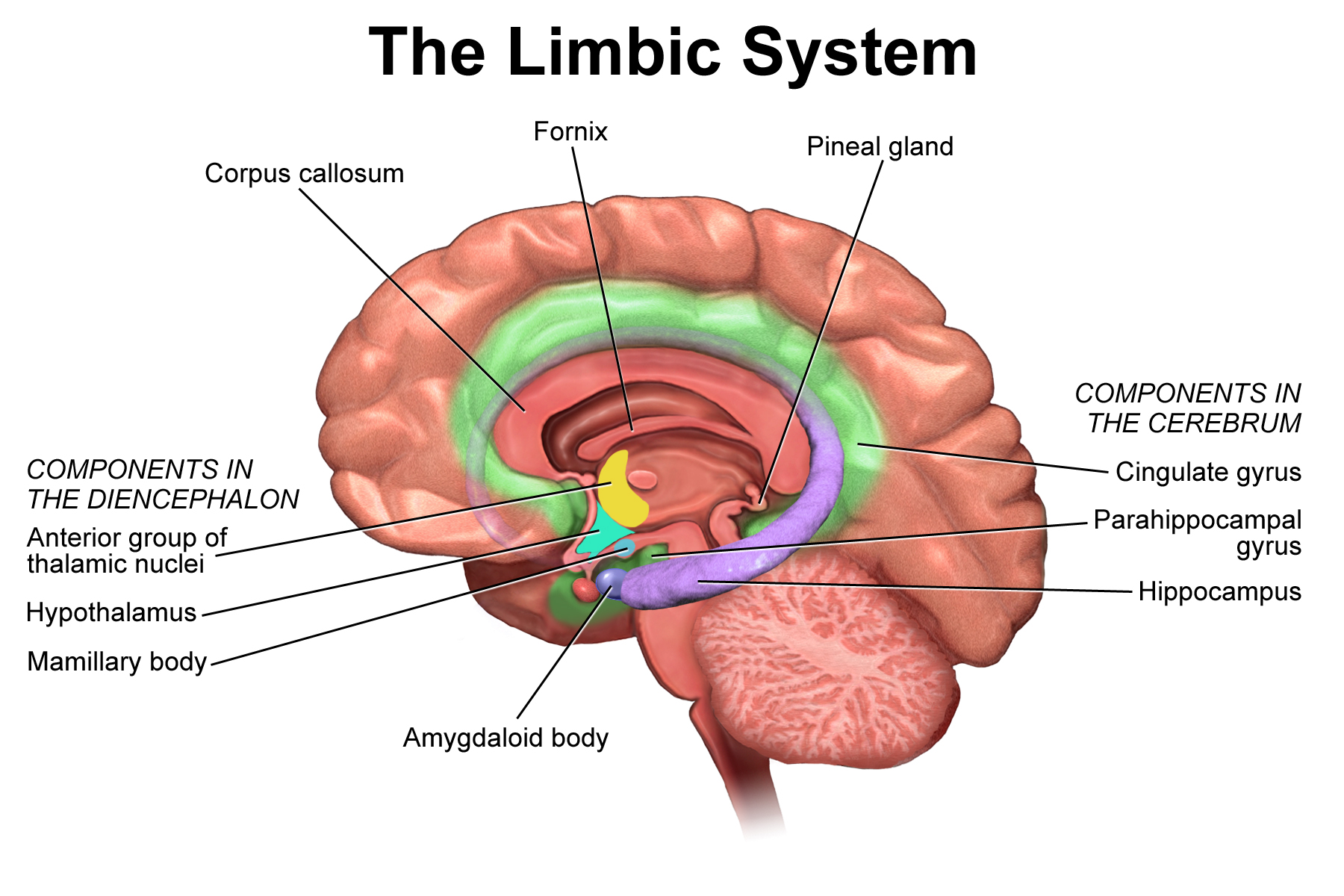

The emotional center of the brain is the limbic system (Figure 6.28), which includes the:

· Thalamus. A relay station to pass on sight, sound, and touch input.

· Hypothalamus. Connects to the peripheral nervous system that controls body states.

· Hippocampus. Acts to lay down memories.

· Amygdala. Analyzes sense and body state input to generate emotions.

· Cingulate gyrus. Links to the cerebral cortex.

Hippocampus damage can result in amnesia, the inability to lay down new memories. Cingulate gyrus damage is involved in depression and schizophrenia. Amygdala damage reduces the ability to process emotions in facial expressions and is a neural marker of autism. The hypothalamus links to the peripheral nervous system, a second brain of a 100 million nerves outside the skull that handles body hormones and digestion. According to three-center theory, the limbic system is a control center, with its own sensory, visceral and memory input, whose role is to generate emotions that activate body states.

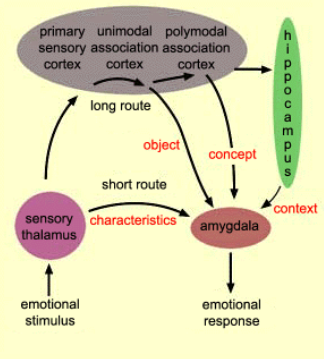

The amygdala can react to facial data in under a tenth of a second, before cortical awareness, by a subcortical visual path (Adolphs, 2008). Sense data from the thalamus goes direct to the amygdala by a short route and takes a long route via the cortex (Figure 6.29), so the amygdala can initiate emotional responses like sweaty hands, dry mouth and tense muscles before the visual cortex even recognizes what is seen. The thalamus still passes data to the cortex, to allow a better but slower decision. Like the movement center, the emotional center uses links that existed when it evolved, so it can act by visceral and sense links acquired before the cortex began to think.

This emotional center even has its own ability to process space. While the hindbrain maps the vector data needed to track movement in space, the midbrain maps the locations needed to return to a point in space (O’Keefe & Nadel, 1978). It can compare its own dedicated sensory and visceral input to past memories to generate the appropriate emotion, as it did for millennia in birds and mammals.

An emotion is a neural representation of reality in body terms generated by the limbic system. For example, fear is the experience of increased heart rate, breathing, adrenaline, blood pressure and blood sugar that accompanies a fight or flight response. Over millions of years, this response to threat was passed on because a body prepared for threat survives it better.

The amygdala interprets facial expressions like anger by emotional learning (Hooker et al., 2006) but also responds to any sensed danger, so an odd smell or an insect crawling on the skin can create a fear response that prepares the body for action. Just as the hindbrain represents reality by schema, and the cortex by thoughts, so the midbrain represents reality by emotions.

Fear isn’t the only emotion, as limbic states support survival in general. Emotions like lust, anger and greed are now primitive urges to be avoided but even today, anger is useful to fight an enemy, lust helps continue the species and greed ensures that surplus food isn’t wasted. Dependence is inappropriate for an adult but it keeps a child by its parents for protection and even laziness has value, as an injured animal should rest and recover. All emotions have survival value in the right situations, as they relate to biological needs.

Emotions, a body-state tool kit that can be tailored to situations based on experience, were a big evolutionary advance at the time. All the emotions we now call negative were useful in evolution and still are, if used correctly. A toolkit is only negative if the wrong tool is used, as if a carpenter uses a hammer to shorten a plank not a saw, it isn’t the toolkit’s fault.

Movement center memory knits sensations into a motor schema but emotional memory lets us base present acts on past experience to allow projection, assessing another’s intent based on what I would do. Many birds cache their food to hide it for use later, but when they see another bird watching them hide food, they return later to re-hide it (Clayton et al., 2007). This ability to understand another’s intent allows empathy, the ability to feel what another feels, a vital component of the emotion we call love.

Doing something is usually better than doing nothing but if a predator is nearby, it’s often better to stay still. For the emotional center to respond to threat by keeping still, it must override the tendency to move, so if a mammal sees a predator, the instinct to run away is stopped by the emotion of fear. When fear freezes an animal in its tracks, the amygdala activates its connections to the brainstem and cerebellum (Ressler, 2010). Mammals have this paralysis by fright response but fish don’t. An emotional center that can suppress hindbrain movement sets the stage for the evolution of cortical control, in the next section.