Some suggest that the physical world is both a computer and its output:

“The universe is not a program running somewhere else. It is a universal computer, and there is nothing outside it.” (Kelly, 2002)

Computers output information but most of the universe doesn’t do that at all (Piccinini, 2007), as the sun outputs light not information.

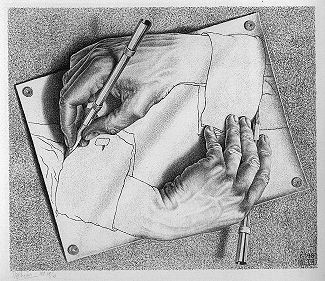

For a computer’s output to also be its only input is a circularity that can crash it. The result is an infinite loop that can’t be stopped so, in simple terms, it hangs. But our universe is constantly changing so it can’t be locked in an infinite loop. Logically, the physical world can no more compute itself than two hands can draw each other (Figure 1.3).

It is equally glib for physicists to talk of quantum processing occurring in space and time:

“Imagine the quantum computation embedded in space and time. Each logic gate now sites at a point in space and time, and the wires represent physical paths along which the quantum bits flow from one point to another.” (Lloyd, 1999) p172.

To embed quantum processing in a fixed space and time contradicts relativity, because it doesn’t allow a fixed space or time. But what began our universe also began its space and time, so if quantum processing did that, it can’t exist in the space and time it created. Only processing that isn’t embedded in our world’s space or time can generate it as a virtual reality.

But could processing create our universe? If our universe is virtual, it must be finite, because what is infinite can’t be computed, and the evidence suggests that it is. Equally all the laws of physics must be calculable, which again they are. An abstract like pi (π) can be infinite as long as it doesn’t represent a physical thing, which it doesn’t. So, our universe could be:

- Calculable: Scientists accept that processing could calculate physical reality based on the Church-Turing thesis, that a finite program can simulate any specifiable output (Tegmark, 2007). This is not determinism, as not all definable mathematics is calculable, e.g. an infinite series. If our world is specifiable, even probabilistically, in theory a program could output it. The idea isn’t that our universe is virtual but that it could be. This option would be falsified by a non-computable law of physics but none has ever been found. Indeed, our world has an algorithmic simplicity beyond all expectations:

“The enormous usefulness of mathematics in the natural sciences is something bordering on the mysterious and there is no rational explanation for it.” (Wigner, 1960)

- Calculating: That some sort of calculating creates physical events is supported by many academics, including main-stream physicists like Wheeler, whose “It from Bit” suggests that processing (bit) can somehow create matter (it). Now processing doesn’t just model the universe, it can cause it (Piccinini, 2007).

- Calculated: That processing actually does cause physical reality is the final step, but few in physics support this “strong” view, that the universe really is a calculated output (Fredkin, 1990).

These statements cumulate as each assumes the previous, so what isn’t calculable can’t be produced by calculating, and what can’t be produced by calculating can’t be a calculated output. It is a slippery slope, as a calculable world that calculating might cause could be calculated, in other words virtual. The second option, that It comes from Bit, sounds good, but that matter causes information that causes matter is circular, and so as impossible as a perpetual motion machine. This reduces the above options to two: either physical reality exists by itself alone and just happen to be amazingly calculable, or it is actually calculated and so virtual. Matter is either a cause or it is caused, with no valid middle ground.