If matter exists, and space is just its absence, is it nothing at all? The greatest minds of physics have wondered whether space exists, and in particular:

If all the matter in the universe disappeared, would space still exist?

If space is something it would, but if it is nothing at all, it wouldn’t. For Newton, space was the canvas upon which God painted, so without matter it would exist as an empty canvas. In contrast, Leibniz didn’t believe that God would make what had no properties, so he defined space relative to matter, just as distance is defined by two marks on a platinum-iridium bar in Paris. It followed that objects only move with respect to each other, so without matter there would be no space.

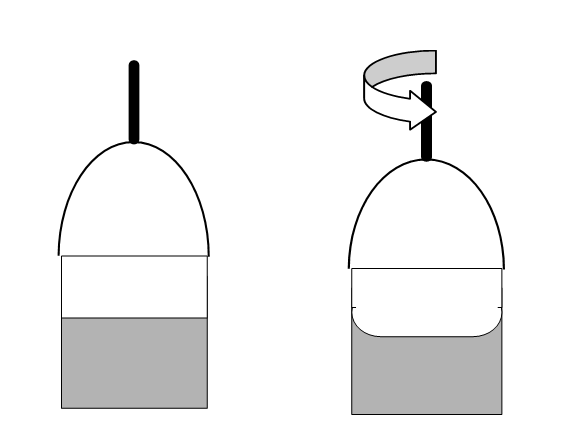

Newton’s reply to Leibniz was a spinning bucket of water (Figure 2.2). At first the bucket spins not the water, then the water also spins and presses up against the side to make a concave surface. If the water spins with respect to another object, what is it? It can’t be the bucket because initially, when it spins relative to the water, the surface is flat, and later, when it is concave, the bucket and the water spin at the same speed. In a universe where all objects move relative to other objects, a spinning bucket should be indistinguishable from one that is still. Another example is an ice skater spinning in a stadium whose arms splay out by the spin. If this movement is relative the stadium, why doesn’t spinning the stadium make the skater’s arms splay? Such examples suggest that the skater is spinning relative to space, not matter (Greene, 2004), p32.

This seemed to settle the matter, so space is something, until Einstein showed that the movement of objects actually is relative. Mach then resurrected Leibniz’s idea to be that the water in Newton’s bucket rotated with respect to all the matter of the universe, so in a truly empty universe it would stay flat and a spinning skater’s arms wouldn’t splay. This theory can’t be tested, because we can’t empty the universe, but his willingness to speculate without evidence shows how disturbing some physicists find the idea that space is:

“…substantial enough to provide the ultimate absolute benchmark for motion.” (Greene, 2004), p37.

The current verdict of physics is that “space-time is a something” (Greene, 2004), p75., so it could be a quantum network output, but how would it register object collisions? Computing suggests two options:

1. Centralized. A central processor registers every object’s absolute position and compares them every cycle to deduce a collision for those at the same point. To its inhabitants, this space would seem to be continuous and to have no existence in itself, but the processing needed increases geometrically with the number of objects as each is compared to every other. For the atoms and electrons in our universe, the load is enormous, so a central processor could overload and collapse the whole system.

2. Decentralized. Each network point is allocated a finite processing capacity to handle local events, so a collision occurs when one gets more processing than it can handle and overloads. To its inhabitants, this space would seem discontinuous and to exist apart from the objects in it. This approach wastes processing on empty space but means that the system as a whole never fails.

Current computing prefers the decentralized option because then the whole system never fails. Our Internet is decentralized for that reason. Given that our universe has run for fourteen billion years without failing, for a virtual space, the second option is expected, that each point of space has a finite capacity to handle whatever passes through it. When nothing does, that processing still runs but gives a null result. Empty space is then null processing not nothing, so if every object disappeared, it would still exist, just as a screen still exists even when it is blank.

It follows that empty space isn’t the passive canvas of Newton, because null processing is active not passive, nor is it the nothingness of Leibniz, because null processing is something not nothing.