The standard model of physics took over a century to build and summarizes:

“… in a remarkably compact form, almost everything we know about the fundamental laws of physics.” (Wilczek, 2008), p164.

It is currently considered by physicists to be:

“…truly the crowning scientific accomplishment of the twentieth century.” (Oerter, 2006), p75.

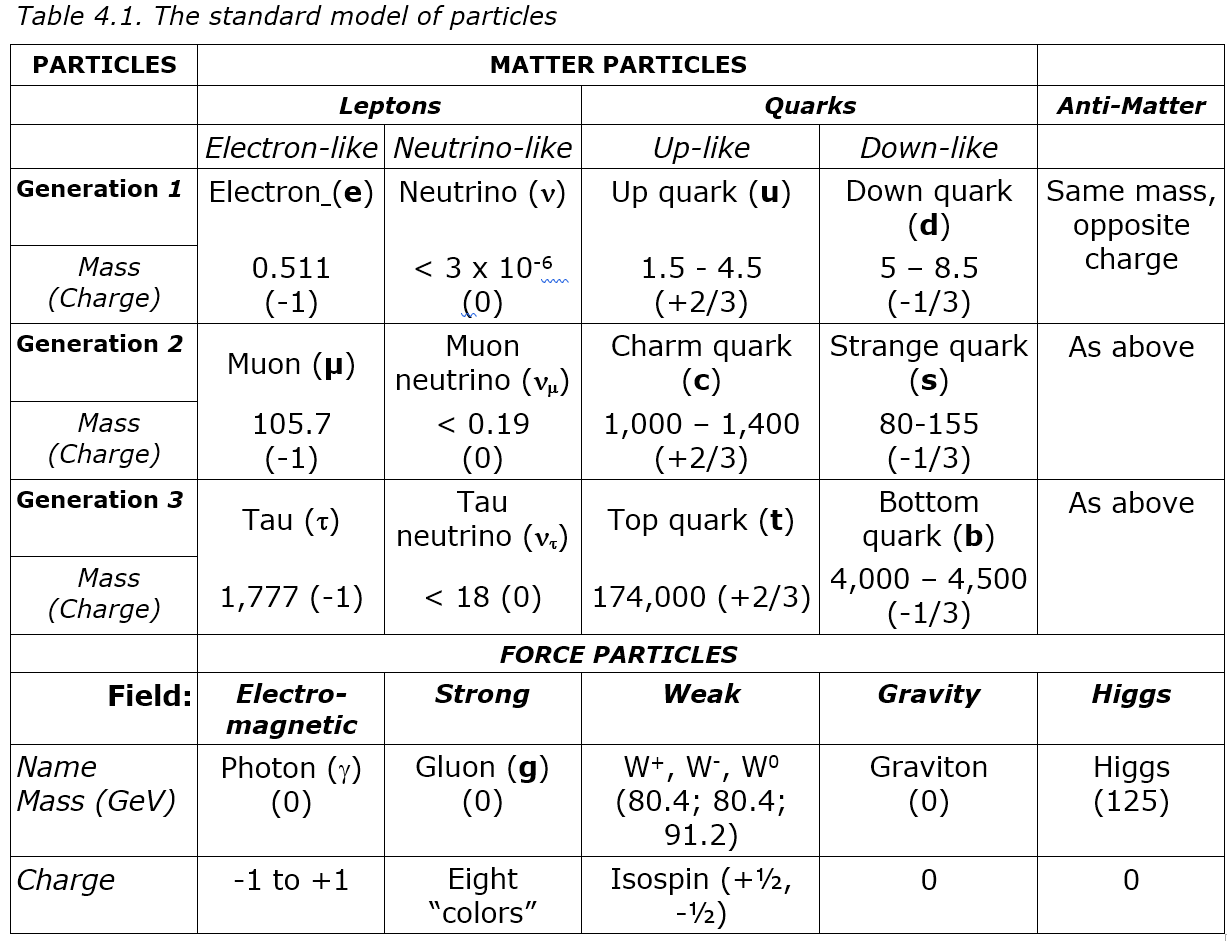

In the standard model, everything is particles that are either made of matter (Fermions) or carry a force (Bosons) (Table 4.1). For example, electrons and quarks are made of matter so they collide with each other, but light is made of bosons that don’t collide. Electrons and quarks should then cause all the mass of an atom, but as will be seen, they don’t.

Matter particles can be like electrons and neutrinos or like up or down quarks, where both also have higher generations for some unknown reason. Up and down quarks then form protons and neutrons that with electrons make the atoms of ordinary matter. Apart from neutrinos that whizz around for no reason, and anti-matter that wasn’t expected, it all seems fairly tidy, but as Woit notes:

“By 1973, physicists had in place what was to become a fantastically successful theory … that was soon to acquire the name of the ‘standard model’. Since that time, the overwhelming triumph of the standard model has been matched by a similarly overwhelming failure to find any way to make further progress on fundamental questions.” (Woit, 2007), p1.

For example, some key questions that the standard model doesn’t answer include:

- Why don’t protons decay as neutrons do?

- Why is our universe made of matter not anti-matter?

- Why do neutrinos have a tiny but variable mass?

- Why do leptons and quarks have three particle generations then no more?

- Why do electrons half spin?

- Why don’t particle masses add like charges do?

- Why do neutrinos always have left-handed spin?

- Why do quarks have one-third charges?

- Why does the force binding quarks increase as they move apart?

- What is the dark matter and dark energy that constitute most of our universe?

It isn’t just that these questions are unanswered, but that over fifty years has seen no progress at all in answering them. The great hopes of string theory and super-symmetry led nowhere, so will the next fifty years be the same? The model now proposed explains not only what the standard model does, but also what it doesn’t, as listed above.