In current biology, evolution is a purposeless process with random outcomes, so re-running it should give different life forms, because randomness doesn’t repeat (Gould, 1990). Yet it can also converge to the same answer, as birds, bats, insects, and fish evolved flight independently, so replaying the evolution of life might give much the same solutions (Morris, 2003).

We can’t reverse time to re-run evolution but we can run evolutionary algorithms, programs that solve problems by imitating evolution. They work by generating an initial population of solutions then evaluating their fitness, to reject those that don’t work. Selected parent solutions are then combined and mutated to produce offspring that are again evaluated, and this repeats until a solution emerges. This method can solve hard problems that logical calculations can’t, and if an answer exists, re-running the algorithm repeatedly finds it. The program has no purpose, and is based on trial-and-error, but it always ends up in the same place, so it isn’t directionless.

Evolutionary potential studies that replay the evolutionary tape with generations of simulated bacteria find that Gould’s theory that evolution never repeats is incorrect (Blount, 2017). Natural selection doesn’t plan ahead but if the solution space is small, it isn’t happenstance either.

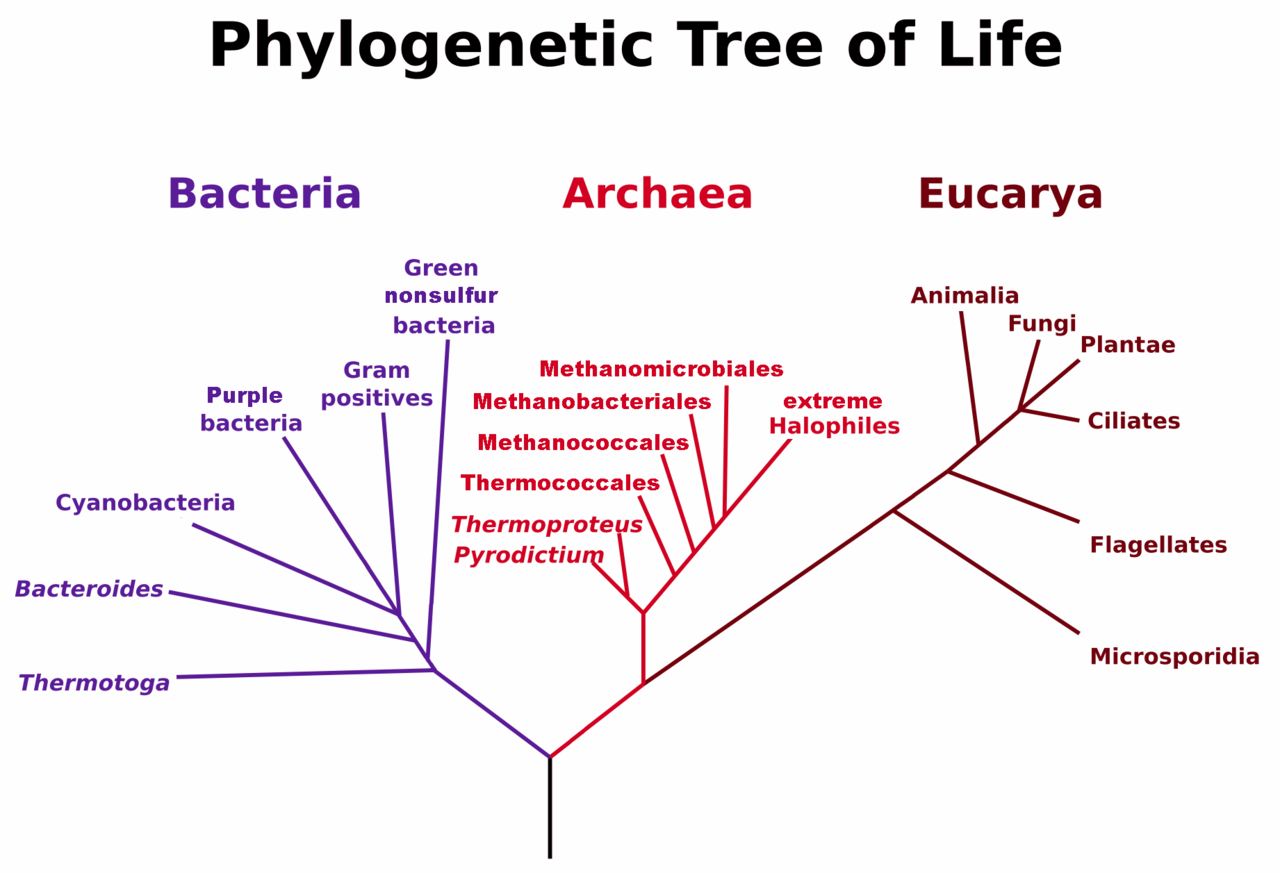

If life then is unlikely, as it is, evolution will find the same solutions, so replaying it will give the same set of answers. Cells will still evolve membranes to help them survive, and replicate themselves to ensure it. Some will discover how to capture solar energy by photo-synthesis, to give plants as primary producers that animals feed on as secondary consumers, and on each other, based on sight, smell, hearing, and mobility by flagella, fins, limbs, or wings. If repeating evolution gives the same results, it has a direction, so it isn’t going nowhere. The direction of evolution can be illustrated by the tree of life because every tree has an up and down direction.

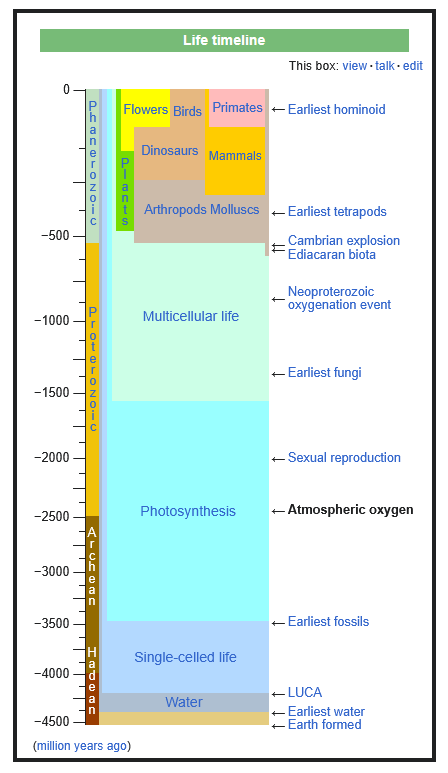

Figure 5.19 represents the solution space for life just as the periodic table does for matter. Cosmogenesis suggests that while hydrogen formed a few million years after the big bang, it took billions more years to make heavy elements like iron that we need to make hemoglobin in our blood. The periodic table represents an evolution where each step decreases entropy to increase order by adding protons and electrons. The evolution of matter then also has a direction, as it will always produce the same periodic table elements. In general, matter and life evolve by the same process, based on finding ordered combinations that survive.

If evolution in general finds combinations that increase order to survive, the number of steps that increase order define its degree. For example in Figure 5.19, simple bacteria and archaea merged into eukaryotes, the modern cells that led to plants and animals (Lane, 2015). This was an order-increasing step because freedom decreases when cells merge, just as it does when protons and electrons merge into atoms. Eukaryotes are then more evolved than bacteria, and they evolved into higher life-forms for the same reason that atoms evolved into molecules like water.

Biology currently argues that bacteria are just as evolved as we are, or more as they have been evolving longer, but time elapsed doesn’t measure evolution. Hydrogen was the first atom, but that doesn’t make it the most evolved. Likewise, human beings are more evolved than bacteria because their ancestry has more order-increasing steps. Evolution is described by a tree not a matrix for a reason, and we are the tip of a new branch while bacteria are at the base. If the height of the tree of life reflected the order-increasing steps of the life timeline (Figure 5.20), the right-hand branch of Figure 5.19 would be much higher than shown.

Yet as Gould says, we are still just a glorious accident. If a meteor hadn’t hit the earth 65 million years ago, to wipe out 75% of all life, mammals would still be small creatures hiding underground in a dinosaur world, and homo sapiens wouldn’t exist. We are an evolutionary accident, but aren’t all its products? The first atom was an accident, as was the first molecule, the first cell, the first plant, and the first animal, so we are no different. Evolution is based on accidents, but the universal trend to increase order isn’t itself accidental. A tree may give fruit here or there by accident, but that fruit will occur isn’t an accident at all.

We are special based on our position on the tree of life, but to think that it exists for us is foolish. 99% of all species that ever lived are extinct today, so if we destroy ourselves, we may join them. Yet even if we explode all our bombs in a nuclear holocaust, in a few thousand years the earth will bloom again, so another species can take our place, as we did that of the dinosaurs. Homo-sapiens was the lucky ape that won the evolutionary lottery, but some species had to because sentient life is possible, so evolution can find it.

Evolution applies all species, as the sun shines on all life, but some call this indifference:

“The universe we observe has precisely the properties we should expect if there is, at bottom, no design, no purpose, no evil and no good, nothing but blind pitiless indifference. … DNA neither knows nor cares. DNA just is. And we dance to its music.” (Dawkins, 1995), p133.

Yet if we all dance to the music of our genes, Dawkins is the same, so why listen to him? This just re-invents the old idea that our universe is a machine in biological terms. Quantum theory debunked that idea last century by letting every photon make choices, and evolution lets creatures do the same, so genes don’t determine our future. Biological nihilism has no more value than physical nihilism, and it fails at the same hurdle, that choice exists.

It is true that the permutations and combinations of life are so vast that no design can predict them, but that is why trying every option is a good strategy. Everything connects, so who knows what has value? For example, fungi are neither plants nor animals but they help forests and gave us penicillin, so they aren’t pointless. Evolution doesn’t make errors as we do because given two paths, it takes both, just as quantum reality does. It does however take time, so while life began almost as soon as it could, the early fossil record has no complex life because it hadn’t evolved yet, but time it seems is something the universe has plenty of.

In conclusion, our universe isn’t a machine designed to manufacture a pre-ordained product like us, but it is evolving to try every possibility, as if it was looking for something. It is like an algorithm set up to solve a problem, but what then is the problem, and how can a virtual reality accomplish it?