Questionnaires. Developing questionnaires is a field in itself, if not an art. See market research for a detailed guide. Yet almost any research that involves people can benefit from questionnaires that are:

- Exploratory. A pre-study questionnaire can discover what concern people.

- Interpretive. A post-study questionnaire can help interpret numeric data.

Key aspects of any questionnaire are its purpose, validity and reliability, questions and responses.

Purpose. Define the questionnaire purpose in advance based on the literature review and research question, i.e. what data do you want to obtain? Then focus on what is important and leave out the rest. People are more likely to finish a short and sweet survey of say 10-20 questions, while too many questions and they just “tick boxes” to get it over with. If the purpose defines a dependent variable don’t forget it, e.g. for research on why people leave a job ask how long they expect to stay in it, as you will correlate all the other reasons for leaving with that.

Validity and reliability. In questionnaires, a valid question is one that measures what you think it does, and a reliable question is one that gives the same results if asked again. Since almost every question has probably been asked before, why re-invent the wheel? Use previous questions with already established validity and reliability if possible, as this also allows cross-study comparisons.

Introduction. The introduction gives the context of the questionnaire, such as who is behind it, why it is important, how long it will take and what the subject gets out of it, if anything. Give time to this, as if subjects don’t answer the questions properly the results will be poor. The introduction is just as important as the questions themselves. Consider giving some minor gift, such as a lottery for free tickets donated by a sponsor, to show commitment. This doesn’t bias the sample as everyone likes a bonus, but check with your ethics committee first. At the very least, offer the reward of them seeing the results somehow.

Question. Good questions engage and are:

- Understandable. Not understanding a question and answering it anyway adds error variance to the results. e. g. “Do you own a tablet computer?” may not be understood by those who don’t know what a tablet computer is. Use simple, clear language with no jargon.

- Unambiguous. Ambiguous questions can be interpreted different ways, e.g.“Do you enjoy and benefit from this web site?” when one might benefit but not enjoy it. Split double-barrelled questions into two questions.

- Unbiased. A biased question implies an answer, e.g. the leading question “Do you prefer healthy foods?” is biased because it suggests the agree answer. Rephrase in an impartial way, e.g. “List 10 foods you eat often”. Equally loaded questions presume an answer that might not apply, e.g. “Why do you drink beer?” is biased because it assumes that all people drink beer.

- Answerable. Only ask questions a person can be expected to answer to, e. g. “How good is the national budget?” is not something most of us know.

- Inoffensive. Using taboo or offensive words may cause a subject to refuse to answer, e. g. “When did you last have sex?” may be inappropriate it some cultures.

Questions that are unclear, ambiguous or ask what isn’t know give error variance, i.e. unreliable data. Questions that are biased or offensive are invalid, e.g. offensive questions often result in missing values. Avoid overly complex questions, e.g. an e-business study asked subject to rate the statement “Our company has e-business applications that are capable of handling significant growth in a number of transactions, customers or employees”. It is hard to understand, as what is “significant” growth” and “a number”? It is also ambiguous as my my company might have good apps for employees but nothing at all for customers or transactions? Check that questions are understandable, unambiguous, unbiased and answerable.

Responses. Question responses can be:

- Open. Respondents answer in their own words. Open responses can give more information but are harder to analyze.

- Closed. Respondents select from a fixed set of answer choices. Closed responses are easier to analyze but harder to design well.

For closed responses, or multi-choice questions, the response scales should be:

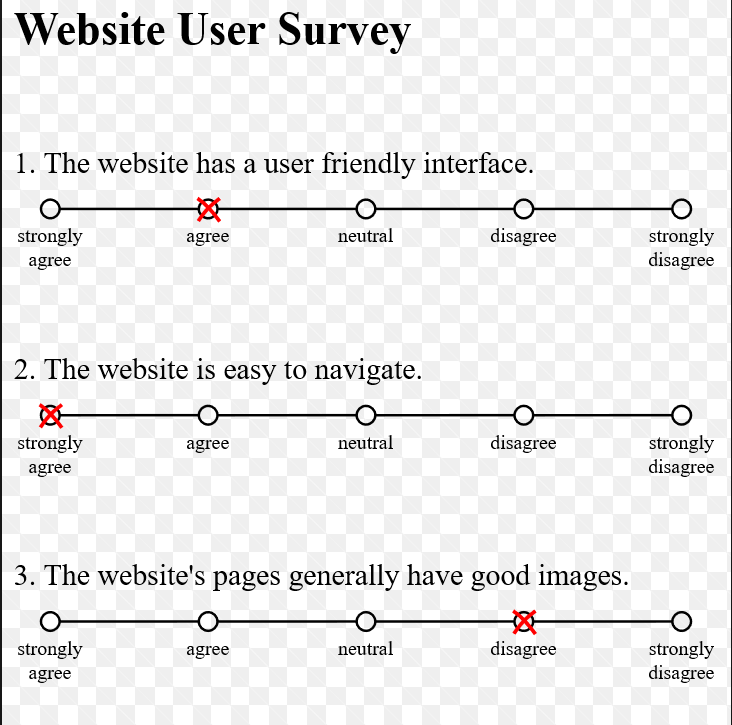

- Understandable.It is obvious what the options mean.Often it is best to individually label each option, as in a 1-5 Likert Scale.

- Unbiased. The choices do not imply a preferred answer. Avoid value laden labels like “better” or “worse”.

- Exhaustive. Options that are collectively exhaustive cover all possible answers.

- Exclusive. Options that are mutually exclusive don’t overlap.

- Sensitive. The choices produce varied user responses.

For example, consider the question “How long have you been at your job?”

- Less than one year

- 1-2 years

- 3-4 years

- More than 4 years

- Don’t know

Is this exclusive and exhaustive? It is not exhaustive because it doesn’t cover those who have worked more than two but less than three years. Now consider the question “How long have you been at your job?”

- Less than one year

- 1-2 years

- 2-3 years

- 3-4 years

- More than 4 years

- Don’t know

This isn’t exclusive as those who have worked two years have two response options not one. Since some will take one option and some the other, this error variance weakens the results. Design response scales to be understandable, unbiased, exhaustive, exclusive and sensitive

Sensitivity. A questionnaire fails if the result is just random error variance, but it also fails if the result is no variance at all, e.g. for the following Likert scale response:

- Strongly disagree

- Disagree

- In the middle

- Agree

- Strongly agree

If everyone chooses In the middle then the question gives no information at all and so is worthless! One can increase the sensitivity of the response scale by making it:

- Strongly disagree

- Disagree

- Slightly disagree

- In the middle

- Slightly agree

- Agree

- Strongly agree

This spreads the response out more to get more value. Increasing the options gives more information but only up to about seven, after which sensitivity increase little. Pilot questions to ensure they are sensitive.

Missing values. When people encounter a question they don’t understand, can’t answer or don’t want to answer, they either tick any box or just leave it out. Both are undesirable. It is better to manage such cases by giving options like Don’t Know or Not Applicable.