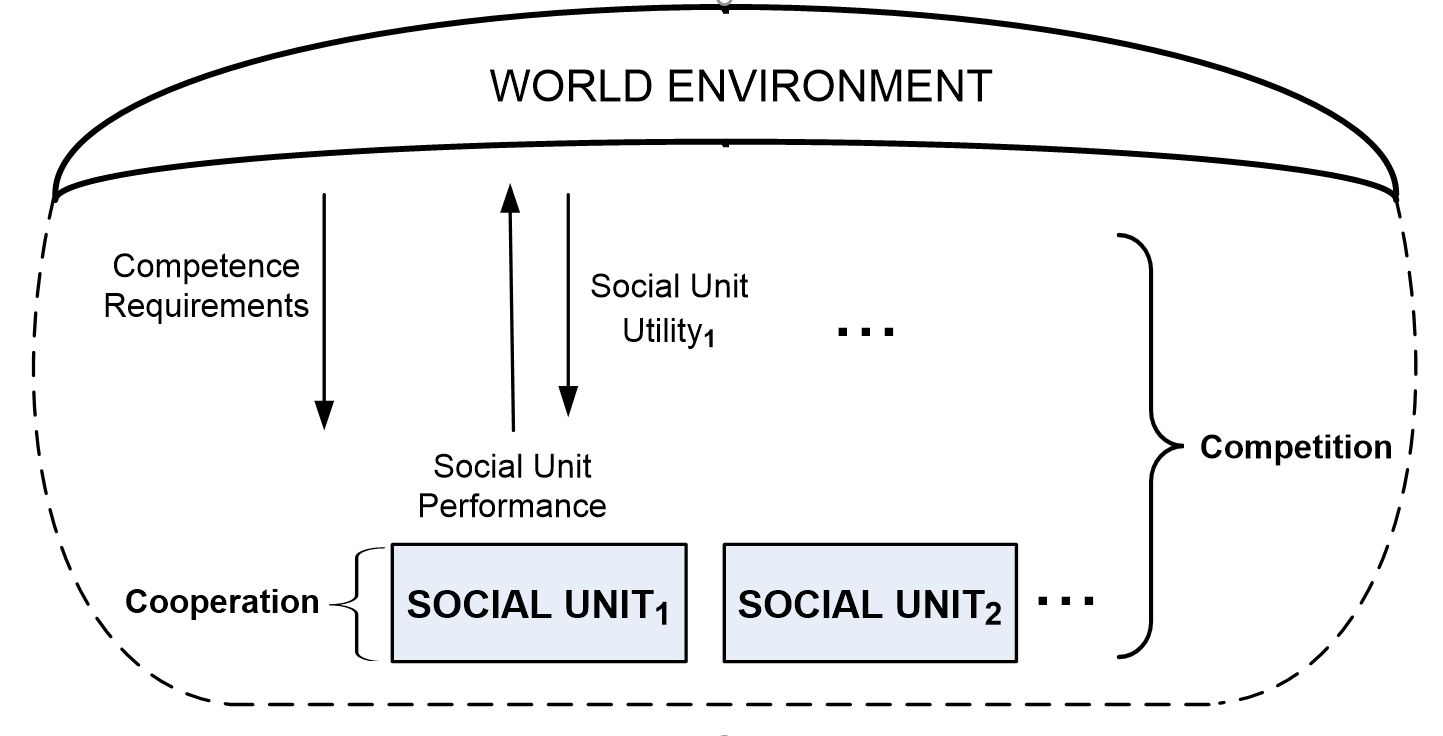

Figure 5.2 shows the Homo-sociologicus model of human behavior, where social units of cooperating individuals compete in a world environment, e.g. tribes or colonies. While competition is evident in nature, cooperation is equally common in the animal kingdom, e.g. social insects like ants form massively cooperative colonies that are so successful they account for at least a third of all insect biomass. In Figure 5.2, the unit that competes and survives is not the individual but the social unit, so soldier ants die protecting an ant colony as they can’t survive without it anyway. The genetics that drives their behavior is based on the colony not the individual, and it evolved because individuals working together create more value than those working alone (Ridley, 1996). Indeed, our body is a colony of cells working together to such a degree that they can no longer survive alone. In this situation, individuals in a social unit perform, in evolutionary terms, based on the sum of the actions of its members.

Biologists now argue for multi-level selection—evolutionary selection for groups as well as individuals (Wilson & Sober, 1994). Social cooperation changes the evolutionary reward rule—individuals still act but the acts selected for are those that give value to the social unit not the individual. This then suggests a social alternative to game theory’s Rule 1:

Rule 2: If a social unit S of { I1, I2 …} individuals faces social action choices {a1, a2 …} with expected social utilities SU(a1), SU(a2), …} then:

If SU(ai) > SU(aj) then prefer ai over aj

In words: In a social unit, individuals prefer acts expected to give more value to the community.

When it is the colony that lives or dies not just the ant, the unit of evolution changes. Value outcomes are calculated for the group as a whole. Natural selection now favors Rule 2, i.e. the evolution of behaviors that help the colony survive. For ants, natural selection favors acts that benefit the community, not the individual ant. Applying Rule 2 to human societies explains the evolution of social acts. Social acts are those that benefit the social unit not the individual; e.g. defending the society even if I might die, as soldiers do, is a social act independent of my individual state. Social castes can be dedicated to social acts, like worker or soldier ants.

Rule 2 applied to human society gives people who prefer acts that benefit the community (Bone, 2005). This is Marx’s communist man, who is politically motivated to common acts that benefit the community as a whole. The psychological basis for this motive is Social Identity Theory (Hogg, 1990), where groups form when members share a common identity, or idea of themselves. If anyone attacks one member of such a group, all group members feel attacked and respond accordingly. Most country’s defense forces work by this rule, as servicemen and women are expected to give their lives for society. To clarify the difference, in Figure 5.1 individuals act according to the benefits for themselves, while in Figure 5.2 they act according to the benefits for the social unit regardless of its effect upon themselves individually. These two pragmatic rules, one at the individual level and one at the community level, both based on evolutionary principles, interact to create social dilemmas.