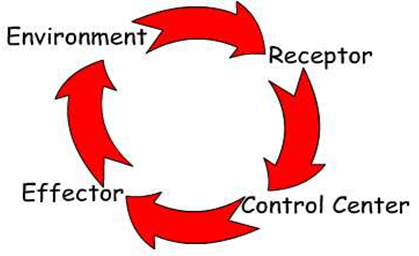

A brain that analyzes input but doesn’t control output doesn’t help survival. It needs access to both input and output, so that when the eyes see danger, the muscles can run from it. The brain must control the basic feedback loop (Figure 6.20) to evolve, but what initiates this loop? Last century, psychology split into two camps on this issue:

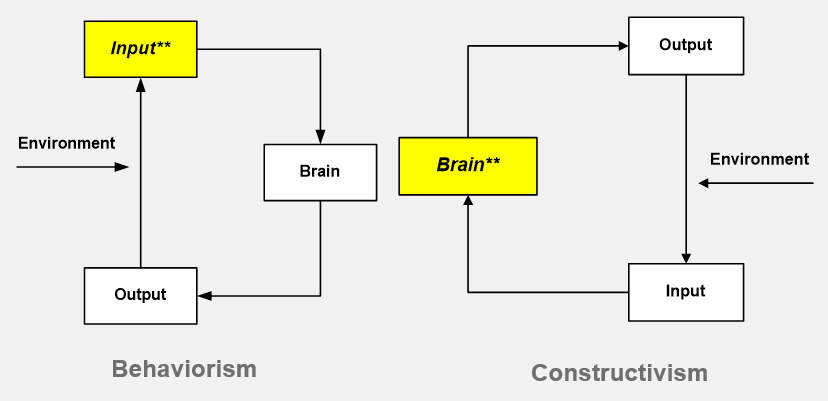

a. Behaviorism argued that people are machines driven by outside events, so stimuli and responses entirely define the loop and what the brain does.

b. Constructivism argued that the brain controls the loop by actively constructing reality, as it can produce more sentences than we could ever learn from stimulus-response associations (Chomsky, 2006).

They differed on what initiated the feedback loop, as behaviorism was input-driven but constructivism was brain-driven (Figure 6.21). Since a circular process can be initiated at any point, today we accept that both can be true. The brain can be driven by outside events but it can also be driven by a brain intent. The second is needed because a brain must initiate the feedback loop to learn or evolve.

Yet updating a running system isn’t easy. When Microsoft upgraded the DOS operating system to Windows, it just replaced it, making it obsolete along with all the time users spent learning it. If nature worked this way, the mammal brain would make the reptile brain obsolete, losing hundreds of millions of years of evolution! Obviously, that is not efficient.

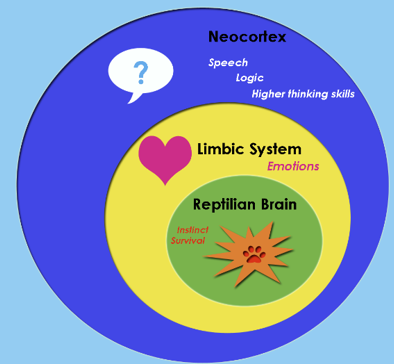

Three-brain theory

That nature doesn’t discard things led an American neuro-physiologist at the National Institute of Mental Health to argue that our brain is a reptile brain overlaid by a mammal brain overlaid by a human brain (MacLean, 1990) (Figure 6.22), where the reptile brain is hind brain structures like the cerebellum, the mammal brain is the mid-brain limbic system, and the human brain is the neocortex of higher thinking. This explained autism as an out-of-control reptile brain and anxiety as an out-of-control mammal brain. In this view, evolution evolved a reptile brain to handle movement, a mammal brain to handle emotions, and finally a neocortex for human thought. MacLean proposed that the human brain is three brains in one, each overlaying the last.

This model then became a popular way to explain autism and animals. Temple Grandin, an authority on animal psychology, who is autistic, wrote:

“To understand why animals seem so different from normal human beings, yet so familiar at the same time, you need to know that the human brain is really three different brains, each one built on top of the previous at three different times in evolutionary history. And here’s the really interesting part: each one of those brains has its own kind of intelligence, its own sense of time and space, its own memory, and its own subjectivity. It’s almost as if we have three different identities inside our heads, not just one.” (Johnson & Grandin, 2006).

The reception of the three-brain model among neuroscientists wasn’t as positive, because evolution doesn’t work by adding layers one after another, like geological structures. As one critic put it: Your brain isn’t an onion with a tiny reptile inside. Evolution didn’t build a reptile brain, then a mammal brain, then a human cortex because it isn’t a linear production line. Nor did it add new things without precedent, as bat wings are modified forelimbs that existed before. And even reptiles have a primitive cortex that lets them care for their young and solve problems (Patton, 2008).

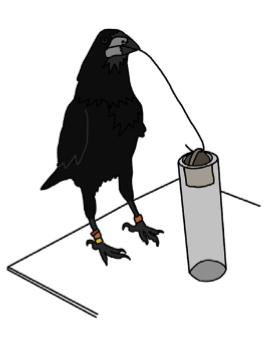

Triune theory also didn’t account for birds. Over millions of years, reptiles evolved into dinosaurs whose descendants today are birds. Birdbrain is a term of ridicule but they are quite smart, as crows can bend a wire into a hook to get food their beak can’t reach (Weir et al., 2002) (Figure 6.23). Children can’t use tools like this until about eight and even then, only half succeed (Cutting et al., 2014). Birds like nutcrackers can hide 30,000 seeds over a 200 square mile area and recover them six months later. Birds are more like feathered apes than reptiles, and urban crows are especially smart:

“On a university campus in Japan, crows and humans line up patiently, waiting for the traffic to halt. When the lights change, the birds hop in front of the cars and place walnuts, which they picked from the adjoining trees, on the road. After the lights turn green again, the birds fly away and vehicles drive over the nuts, cracking them open. The birds wait patiently with human pedestrians for a red light before retrieving their prize. If the cars miss the nuts, the birds sometimes hop back and put them somewhere else on the road.” (Earthfire Institute)

Birds share many cognitive abilities with advanced mammals but their brains evolved differently (Jarvis & et al., 2005), as the bird cortex is smooth while the mammal cortex is folded. The current view is that as bird and mammal brains evolved from the basic reptile design, nature tried both options and converged to equivalent functions (Lefebvre et al., 2004). Triune theory doesn’t predict this evolution, but an alternative that does is now explored.