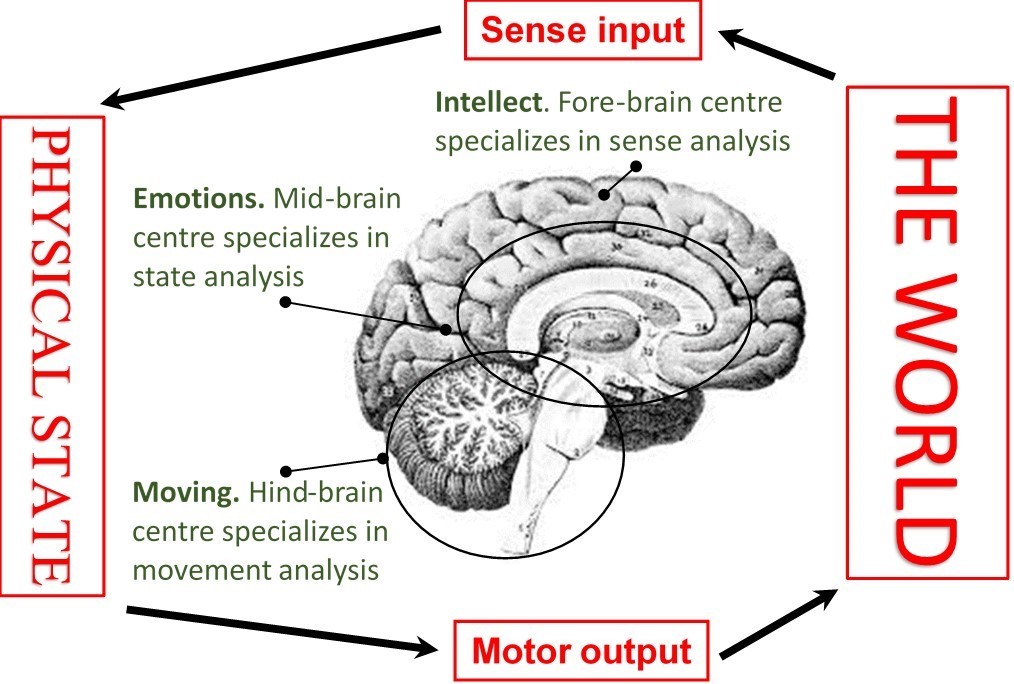

The human brain doesn’t have an instruction manual but if it did, it might stress that having many ways to control the feedback loop is a feature not a bug. Brains have to analyze sense input, body state and muscle output anyway, so three specialists survive better than one (Figure 6.33). If the brain had only one control center, it would be the hindbrain that matured first not the cortex that came later. This division lets the movement center manage movement details, the emotional center manage feelings, and the intellectual center manage thoughts. But our brains must use the right specialist for the job to succeed.

In Figure 6.33, the forebrain that receives muscle input is next to the motor nerves for those muscles, like a single input-output gate. In fish, the cerebellum used this gate to run the brain-world feedback loop, with data from the still evolving forebrain and midbrain. In birds and mammals, limbic control can override the cerebellum, which still managed fine motor control. In later mammals like us, the neocortex became independent, but its control of emotions and instincts is often quite limited.

The result is a brain with not one control-center but three. Each center monitors body and sense input with its own neural connections, and does what it decides is best. Evolution has given us a brain with super-fast movement, powerful emotions, and complex thoughts, because different situations need all three. This isn’t easy because the centers can’t “talk” to each other as people do. They all speak different “languages” because millions of years of evolution separate them.

For example, people with a spider phobia can discuss their fear intellectually and accept that a little harmless spider isn’t a threat. They have all the data needed for a non-fear response, but putting that spider on the table still makes them jump up in fear! The emotional center ignores talk but an actual spider makes it press the red danger button. And if during the conversation an object fell from a shelf above, the moving center might catch it before the intellect can recognize it. Different brain centers are too busy constantly analyzing external events to talk internally.

Each center must learn independently. For example, falling on a hard surface is a common cause of injury in old people. It happens so fast that what the brain does in a fraction of second decides whether we end up injured or just get back up. The intellect is too slow to act in time and an emotional center panic isn’t much use, as a muscle spasm can injure bones or joints more than the fall itself. In most cases, its best to relax and let the movement center manage the fall, as parachutists do. This is easy to say but it takes a lot of practice to learn.

The three-in-one answer that evolved from the early forebrain-midbrain-hindbrain division gives us fast responses, powerful emotions, and complex thoughts. The traditional idea of human nature as intellect, emotions and will derives from this early neural division of labor. The three-center approach to the brain can be illustrated by a story:

Once upon a time there were three brothers who flew a tiny plane. Elder brother handled the flight controls, middle brother monitored the cockpit knobs, and baby brother looked out the window to see what was out there. Eventually, by delivering goods in the city to earn money, they managed to buy a jet plane for intercity travel that had knobs to automate landing, takeoff, and flight among other things. This meant that middle brother was more often in charge but elder brother still monitored the controls to make fine adjustments and took over in emergencies. Middle brother had a thrust button for more power but he had to use it at the right time. As little brother grew older, he used what he called ‘symbols’ to record events on bits of paper but the others just used his spotting ability.

Intercity travel made more money, so one day they bought an intercontinental jet with state-of-the-art computer controls. Elder brother preferred his manual controls and middle brother liked his dials and knobs but younger brother preferred the computer screen to paper. It took longer but he could control the plane with it and even send messages to other planes. His older brothers were too busy to talk in flight, so he would demo a new flight technique by computer control and they picked it up if useful.

Their plane was constantly being upgraded. At first, elder brother used a simple dot radar to avoid colliding with other planes. When a radar with pictures instead of dots was installed, he found it too complex for manual flying but middle brother used it to identify friend from foe. When computer radar arrived, the first two found it complex and slow but little brother used it to analyze trends and causes. Over time, the brother’s plane dominated the airways because three pilots are better than one if each does what they are good at.

Our brain has three centers just as cars have different gears for different situations, but why do we experience one driver? All that neuroscience knows about the brain, from blindsight to the split-brain, suggests many “I”s not one. Our sense of “I” implies that nerve input goes to a center that then directs all motor nerves, but neuroscience assures us that this isn’t so:

“In contrast to this first-person experience of a unified self, modern neuroscience reveals that each brain has hundreds of parts, each of which has evolved to do specific jobs – some recognize faces, others tell muscles to execute actions, some formulate goals and plans, and yet others store memories for later integration with sensory input and subsequent action.” (Nunez, 2016) p55.

This issue, of how different brain areas work together, is called the binding problem.