Objects tend to move in a straight line, defined as the shortest distance between two points. The general term is geodesic because on a curved surface like the earth, the shortest distance between the poles is a curved longitude. A geodesic is a straight line on a curved surface, but why do objects move in straight lines in the first place?

Billiard balls on a table are said to move in straight lines by a property of matter called inertia, the tendency to continue in the same direction. Inertia then makes an arrow shot into the air fly up. But then it falls to the ground, so Newton suggested that a force from the earth pulled it down, called gravity. The arrow then moved according to the forces of inertia plus gravity, with space just a passive context. In classical physics, inertia makes objects move in straight lines unless another force is acting. It followed that inertia and gravity, both properties of matter, determined how objects move.

Einstein then showed that gravity works by curving space, to alter the geodesic, so an arrow fired into the air actually still moves in a straight line. We see a curve because space itself is curving, just as a globe longitude is curved but still the shortest distance between the poles. If the earth curves space around it to cause gravity, the moon then orbits the earth because that is its straight line. This changes the logic, as now gravity isn’t a force acting on an object, but a change in space that alters what a straight line is. It follows that inertia could also be a property of space, not the object itself.

How a wave moves on a network depends on how it is passed on, so if space is a network that transmits waves, light moves in a straight line because that is how it is passed on. Light then moves in a straight line because of space, and continues to do so unless something alters space. To understand how this could be, suppose that:

“A point in spacetime is … represented by the set of light rays that passes through it.” (S. Hawking & Penrose, 1996), p110.

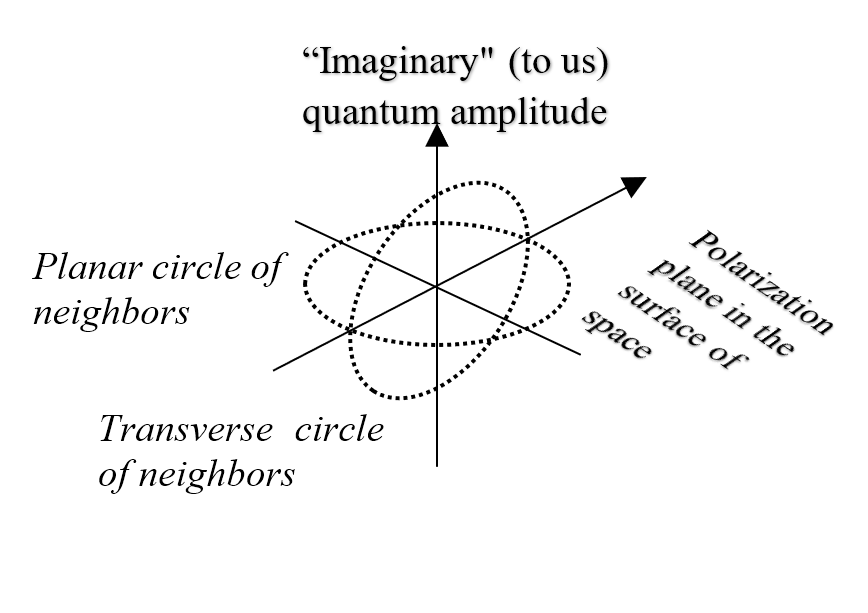

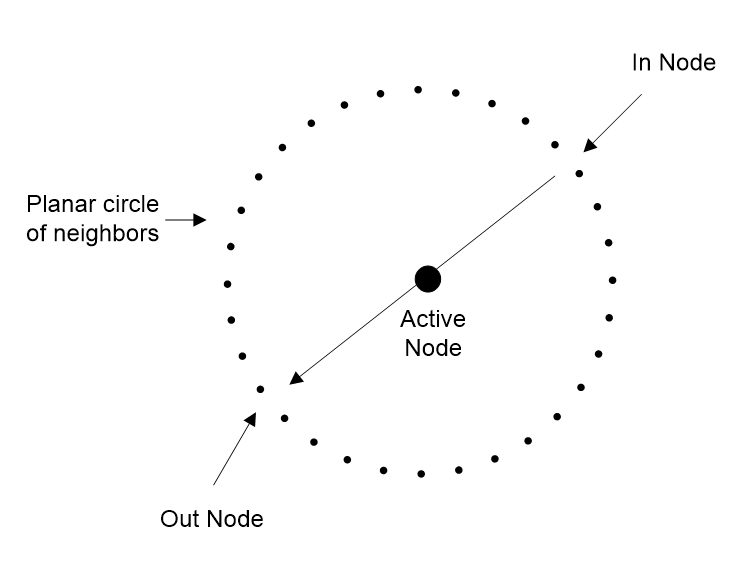

If these rays represent the connections of a point to its neighbors, its possible transfer directions are a sphere around it. But if a photon is a transverse wave, it can only move at right angles to its vibration direction, so its directions are a circle not a sphere. Hence, every photon has a polarization plane at right angles to its vibration that limits how it moves through a point to a planar circle (Figure 2.8), as it must enter from and exit to points on that circle. Planar circles simplify how photons are passed on by a point, just as planar anyons simplify the quantum Hall effect (Collins, 2006).

Why then does light move in straight lines? For a network, the shortest path between any two points is the one with the fewest transfers, which is also the fastest path. For a wave spreading in every direction, the fastest path to any point is a straight line. Light will then move in a straight line to any point if it always takes the fastest route, which it does.

Chapter 3 gives the details, but essentially light travels in a straight line because its waves take every path to a destination and the first to arrive triggers a physical event. It follows that light moves in a straight line by a property of space, not itself. Chapter 4 extends this conclusion to matter objects, and Chapter 5 explains how gravity alters space, as Einstein said. The classical view that things move by their own inclination within a space of nothing is thus replaced by the view that they move according to how the network of space passes them on.

In conclusion, a quantum network can generate a space like ours based on rotations. The resulting polar space explains how space expands, how objects move, and how light vibrates, better than the linear space of Euclid. If the geometry of the universe is based on circles not squares, then for a point, planar circles specify how light is passed on and transverse circles specify how it vibrates (Figure 2.9). In the next section, transverse circles define time, just as planar circles define space.