In the standard model, an electron exists at a point that occupies no space, but how can it then have mass? A particle’s mass should come from its substance, but a particle with no size can’t have a substance, so the idea that electron particles have mass but no size seems seriously flawed. But if an electron is processing in some form, as light was in the last chapter, it can exist at a network point that, like a screen pixel, occupies a space but can’t be divided.

Our networks transfer data by communication channels, where each channel handles different data just as different TV channels present different shows. If the quantum network is the same, when light passes through a point in space, one photon is handled by one channel, and another photon polarization is another channel, so there are many channels per point. And as our channels are mostly duplex (they work in both directions), we expect the same here. Finally, every channel has a finite bandwidth, which in this model is the quantum process defined earlier (3.3.1). Based on this logic, each channel of a point of space can:

1. Accept one photon with one polarization coming from one direction.

2. And at the same time accept a photon with the same polarization from the opposite direction.

3. Up to a bandwidth of one quantum process per cycle.

One channel is then represented by a line through a point, plus a plane cutting it to represent the polarization it accepts. Hence, if two photons with the same polarization enter a point from opposite directions, one channel can handle both, up to its bandwidth of one quantum process. Since each photon is a quantum process spread over many points, light rays in general don’t collide, as is observed, but this approach suggests an exception.

One photon is one quantum process distributed over its wavelength, and the channel bandwidth is also a quantum process, so photons don’t usually overload it, but if high frequency photons that divide over two points meet, the channel will overload. Note that this wavelength, of two Planck lengths, is the shortest possible, because one process at one point is empty space. Now let an extreme photon be one that is distributed over two network points. Each point runs half a quantum process, so two extreme photons meeting head-on in a channel will overload it’s one process bandwidth, so instead passing through each other, they will collide in a physical event.

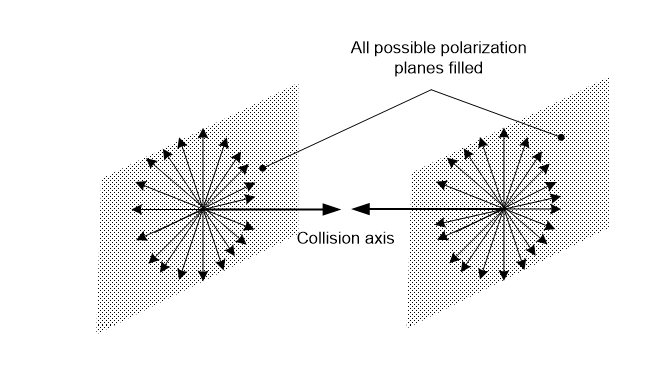

Yet a photon spins on its movement axis, so it can just restart in another channel, but what if every channel overloads? If rays of light with extreme photons in every polarization plane meet head-on at a point, every channel on the axis will overload at the same time (Figure 4.2). There are no free channels for the photons to carry on, so they must restart at that point. This result is unlikely, but extreme light was common in the first plasma, so by the law of all action 3.6.3), it had to occur because it is possible.

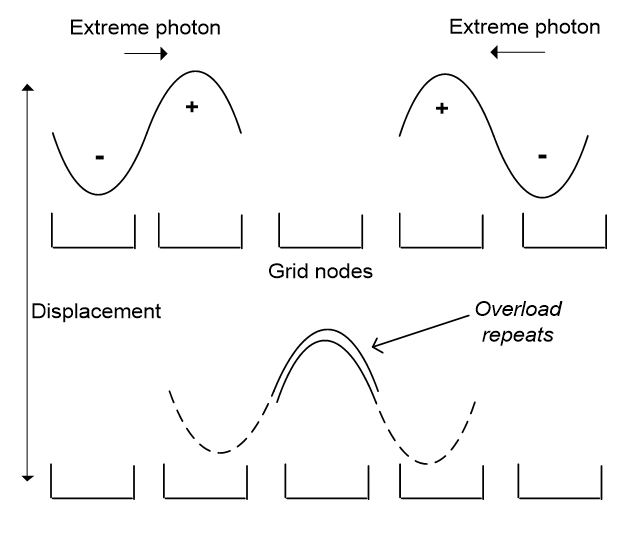

Figure 4.3 shows the result for one channel, with every channel the same. Now if a photon head is its leading half, and its tail is the following half, two heads meeting that each request half a quantum process will overload the channel bandwidth of one. These photons then restart in the next cycle, to set off in opposite directions, but again collide in another overload that restarts them again, and so on. This recurring overload repeats every cycle because every channel is the same. The network that once hosted only waves now has a constant processing bump, which is an electron.

The result is stable, because any photon arriving on that axis finds all the channels taken, while a photon arriving at right angles passes through it by a different channel. An electron is then a repeating overload, like a stuck record that keeps repeating the same song, and its mass is the net processing that repeats.

Is such a repetition possible for quantum waves? In experiments, electro-magnetic waves can repeatedly interact to form static states (Audretch, 2004, p23), as frequent observations maintain the quantum state if the time delay is short (Itao, Heizen, Bollinger, & Wineand, 1990). Feynman’s PhD partitioned the electron wave equation into opposing advanced and retarded waves, but he didn’t pursue it. Other theories that let waves oppose include Wheeler–Feynman’s absorber theory, where retarded and advanced waves give rise to charge (Wheeler & Feynman, 1945), Cramer’s transaction theory of retarded and advanced waves (Cramer, 1986), and Wolff‘s idea that electrons are in-out spherical waves (Wolff, 2001). If quantum waves form standing waves as other waves do (Figure 4.4), an electron could be a standing wave created by extreme light.

This conclusion contradicts the standard model in several ways. Instead of a particle of matter with no size, which makes no sense, an electron now runs at a network point that has a size, just as a screen pixel does. Instead of having no structure, an electron is now a one-axis collision. Instead of matter being an inert substance, it is now light pulsing constantly in a never-ending loop. Matter is then light stuck at a point, in a standing wave of light that seems static but is actually active. However as this result only applies to one axis, an electron is just one-dimensional matter.

When a computer process hangs in an infinite loop that a restart can’t fix, we call it a glitch, but for the quantum network, the matter glitch was an evolution not an error.