Lambert’s cosine law is that the intensity of light hitting a surface varies by the cosine of the angle it hits at, so light at right angles to a surface gives all its intensity, but light parallel to it gives none. Light at right angles is 90º, whose cosine is one, and parallel light is 0º, whose cosine is zero, and in between, light projects an intensity according to the cosine of its angle.

In processing terms, a ray of light can access all the channels of a point on its axis, but also projects onto channels on other axes according to angle by the cosine law. Rays of light on the same axis then compete for the same channels, while rays at right angles don’t compete for channels at all, and in between, they compete for channels based on the cosine of the angle between them.

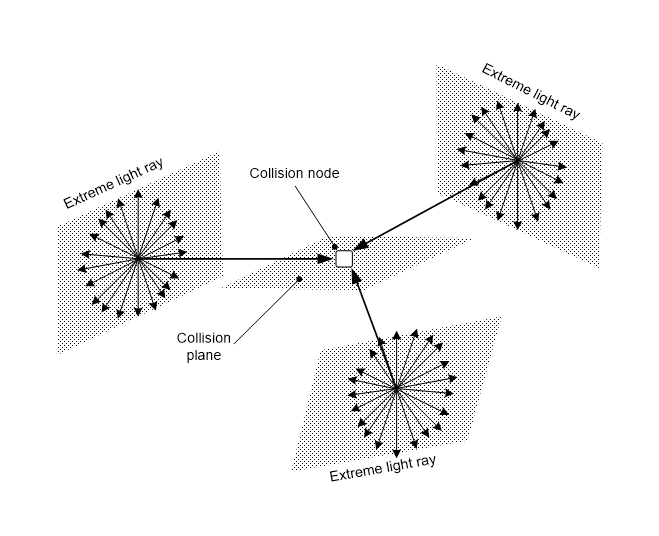

For electrons, two extreme light rays overload the channels of a line through a point, so what can three extreme rays do for a plane? Can quarks arise in the same way that electrons did? Previously, the bandwidth of a line through a point was taken to be one, so the bandwidth of a plane through a point will be two. Hence, if two extreme light rays fill the channels of a line through a point, four rays are needed to fill a plane through it.

In Figure 4.9, three equal-angle extreme rays meeting at a point can’t fill the bandwidth of a plane. Each ray fills half of its line axis bandwidth but three times a half is 1.5 not two, so the result isn’t stable as there are unfilled channels that another entity could exploit. Dividing the plane bandwidth of two between three axes gives each a two-thirds bandwidth.

Yet three rays can fill two axis to be semi-stable, as quarks are, so a quark could be when a three-way interaction fills two axes but leaves the third unfilled.