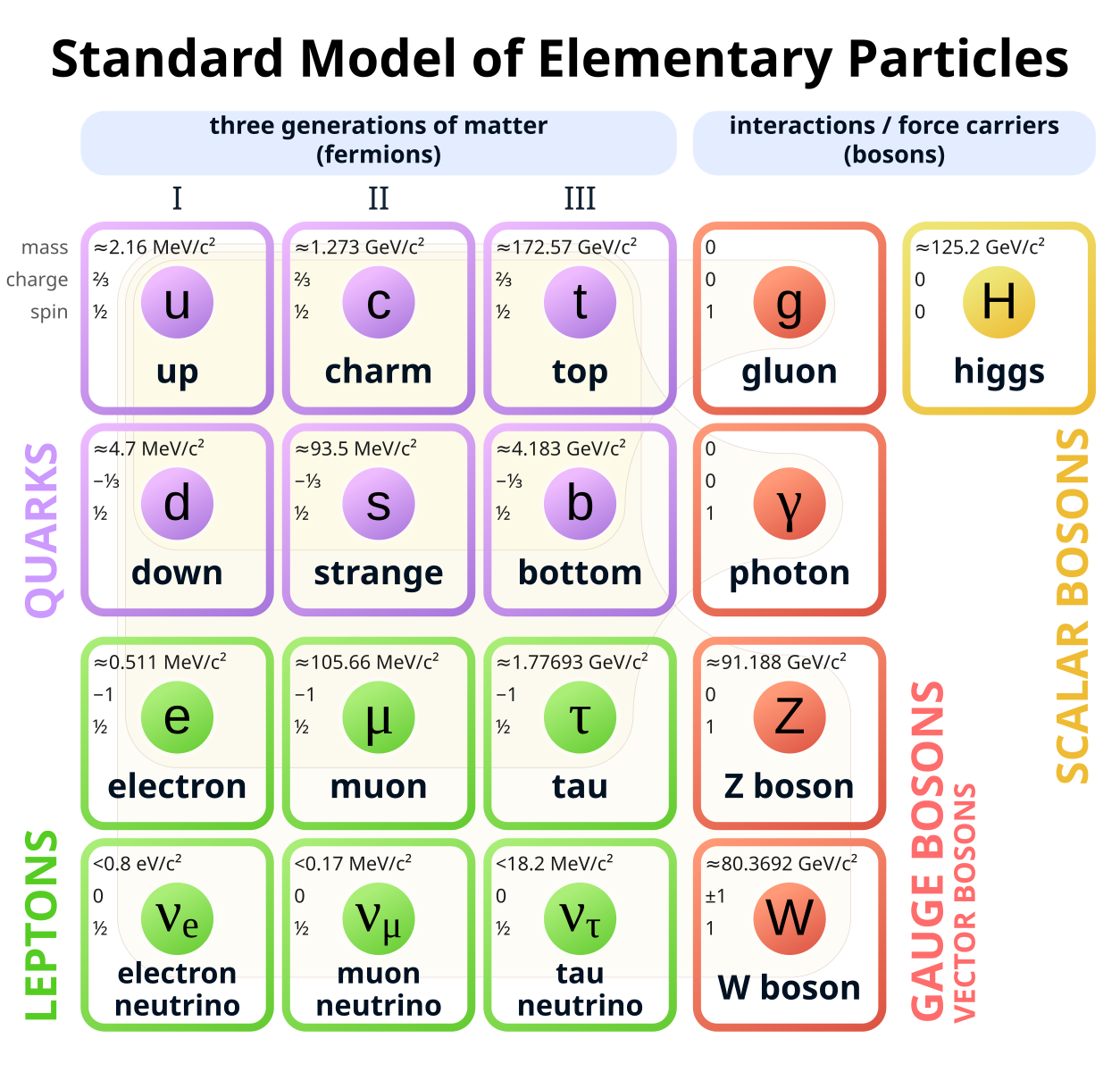

A matter substance should break down into basic bits so last century physics collided matter to find what doesn’t break down further, which it called elementary particles (see Figure).

A matter substance should break down into basic bits so last century physics collided matter to find what doesn’t break down further, which it called elementary particles (see Figure).

Yet when pressed on what these particles actually are, experts retreat to equations that don’t describe particles at all. This bait-and-switch, talking about particles but giving wave equations, is now standard practice. The equations describe quantum waves not particles, but we see particles! Feynman explains how this double-speak began:

“In fact, both objects (electrons and photons) behave somewhat like waves and somewhat like particles. In order to save ourselves from inventing new words such as wavicles, we have chosen to call these objects particles.” (Richard Feynman, 1985), p85.

Yet if engineers said “This vehicle has two wheels like a bicycle and an engine like a car, so to avoid inventing a new word like motorcycle, we have chosen to call it a car”, who would accept that? Physicists with accelerators seem to see everything as a particle as a boy with a hammer sees everything as a nail, but what was actually found was:

1. Ephemeral. The standard model tau particle is just a million, million, millionth of a second energy spike. A lightning bolt is longer than that but it isn’t a particle, so why is a tau? A flash isn’t a particle!

2. Transformable. When a neutron decays into a proton and an electron, three elementary particles become four, so how can they be elementary?

3. Massive. A top quark has the same mass as a gold nucleus of 79 protons and 118 neutrons but it plays no part in the universe we see, so how is it elementary?

4. Unstable. Top quarks also instantly decay, but calling what decays elementary is a strange use of the term.

Particles that decay and transform into each other aren’t elementary because what is elementary shouldn’t do that. Equally, energy events that last less than a millionth of a second aren’t particles because particles should last longer than that. The elementary particles of the standard model are then neither elementary nor particles.

Calling them building blocks doesn’t work either, as how can one build a house from bricks that only exist for a moment, or instantly decay, or transform into other bricks? And why have a building block that is bigger than most houses? Of all these building blocks, only the electron is stable alone, and it adds hardly anything to the mass of an atom.

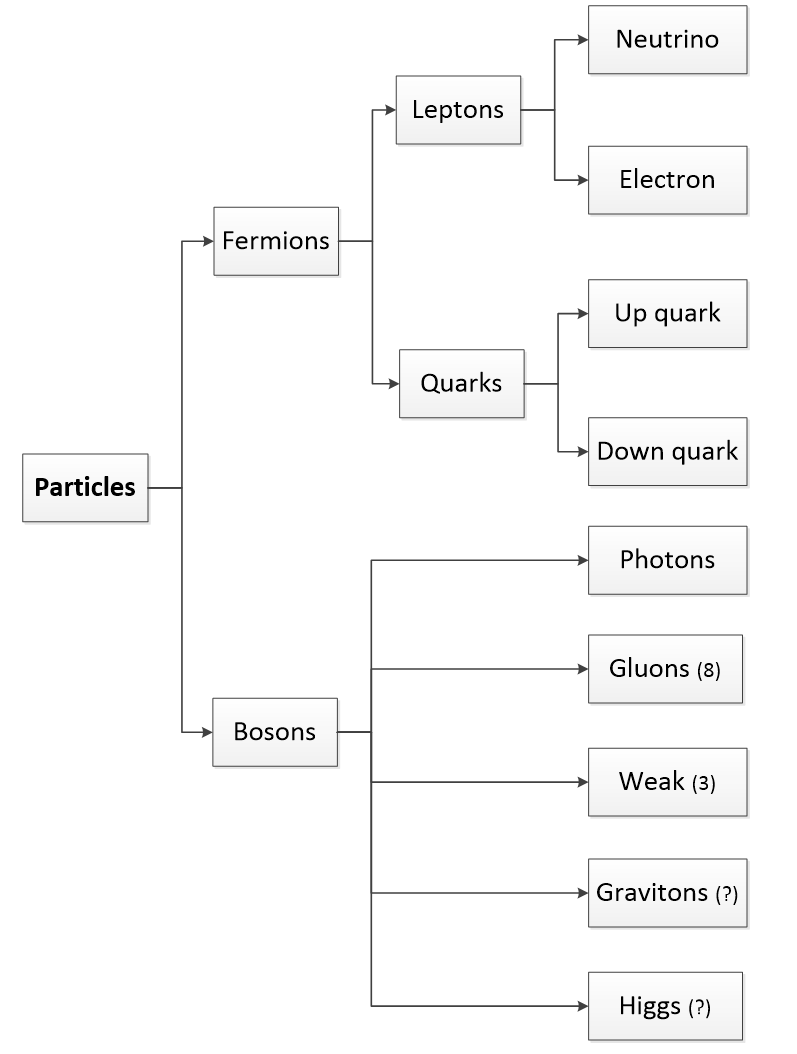

In Figure 4.18, the standard model divides its particles into fermions that cause matter and bosons that cause forces. This, we are told, is the end of the story, because accelerators can’t break matter down further, but how do particles that exist at a point take up space? Apparently, virtual particles from fields keep them apart but this theory can’t be tested because virtual particles can’t be observed.

The standard particle model satisfies neither logic nor science, but survives because we don’t look behind the curtain of physical reality. The wizard of Oz told Dorothy: “Pay no attention to that man behind the curtain” to distract her from the real cause of events, just as today’s wizards tell us to ignore the quantum waves that actually cause physical events.