Research questions from the list below and give your answer, with reasons and examples. If you are reading this chapter as part of a class – either at a university or in a commercial course – work in pairs then report back to the class.

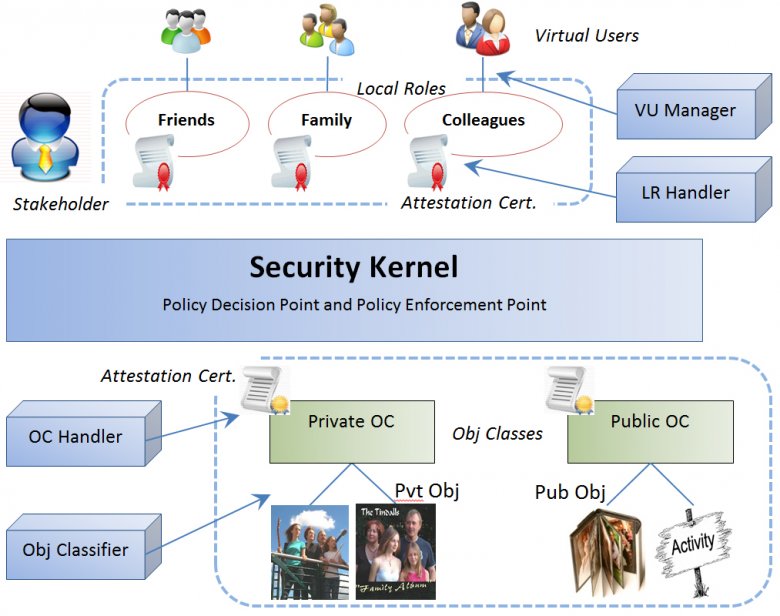

1) What is access control? What types of computer systems use it? Which do not? How does it traditionally work? What is the social network challenge and how has access control responded?

2) What is a right in human terms? Is it a directive? How can rights be represented as information? Give examples. What is a transmitted right called? Give examples.

3) What is the difference between a user and an actor? Contrast user goals and actor goals. Why are actors necessary for online community evolution?

4) Is a person always a citizen? How do communities hold citizens to account? If a car runs over a dog, is the car accountable? Why is the driver accountable? If online software cheats a person, is the software accountable? If not, who is? If automated bidding programs crash the stock market and millions lose their jobs, who is accountable? Can we blame technology for this?

5) Contrast an entity and an operation. What is a social entity? Is an online persona a person? How is a persona activated? Is this like “possessing” an online body? Is the persona “really” you? If a program activated your persona, would it be an online zombie?

6) What online programs greet you by name? Do you like that? If an online banking web site welcomes you by name each time, does that improve your relationship with it? Can such a web site be a friend?

7) Compare how many hours a day you interact with people via technology vs. the time spent interacting with programs alone? Be honest. Can any of the latter be called conversations? Give an example. Are any online programs your friend? Try out an online computer conversation, e.g. with Siri, the iPhone app. Ask it to be your personal friend and report the conversation. Would you like a personal AI friend?

8) Must all rights be allocated? Explain why? What manages online rights? Are AI programs accountable for rights allocated to them? In the USS Vincennes tragedy, a computer program shot down an Iranian civilian airliner. Why was it not held to account? What actually happened and what changed afterwards?

9) Who should own a persona and why? For three social technical systems, create a new persona, use it to communicate, then try to edit it and delete it. Compare what properties you can and cannot change. If you delete it entirely, what remains? Can you resurrect it?

10) Describe two ways to join an online community and give examples. Which is easier? More secure?

11) Describe, with examples, current technical responses to the social problems of persona abandonment, transfer, sharing and orphaning. What do you recommend in each case?

12) Why is choice over displaying oneself to others important for social beings? What is the right to control this called? Who has the right to display your name in a telephone listing? Who has the right to remove it? Does the same apply to an online registry listing? Investigate three online cases and report what they do.

13) How do information entities differ from objects? How do spaces differ from items? What is the object hierarchy and how does it arise? What is the first space? What operations apply to spaces but not items? What operations apply to items but not spaces? Can an item become a space? Can a space become an item? Give examples.

14) How do comments differ from messages? Define the right to comment as an access triad. If a comment becomes a space, what is it called? Demonstrate with three commenting social technical systems. Describe how systems with “deep” commenting (comments on comments, etc.) work. Look at who adds the depth. Compare such systems to chats and blogs – what is the main difference?

15) For each operation set below, explain the differences, give examples, and add a variant to each set:

a. Delete: Delete, undelete, destroy.

b. Edit: Edit, append, version, revert.

c. Create: Create.

Define a fourth operation set.

16) Is viewing an object an act upon it? Is viewing a person an act upon them? How is viewing a social act? Can viewing an online object be a social act? Why is viewing necessary for social accountability?

17) What is communication? Is a transfer like a download a communication? Why does social communication require mutual consent? What happens if it is not mutual? How does opening a channel differ from sending a message? Describe online systems that enable channel control.

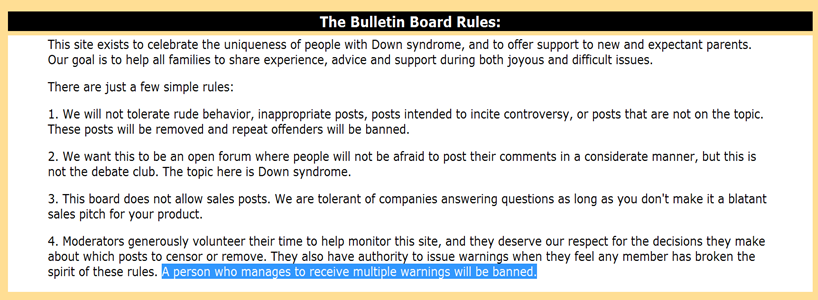

18) Answer the following for three different but well known communication systems: Can a sender be anonymous to a receiver? Can a receiver be anonymous to a sender? Can senders or receivers be anonymous to moderators? Can senders or receivers be anonymous to the transmission system?

19) Answer the following for a landline phone, mobile phone and Skype: How does the communication request manifest? What information does a receiver get and what choices do they have? What happens to anonymous senders? How does one create an address list? What else is different?

20) What is a role? Can it be empty or null? Give role examples from three popular social technical systems. For each, give the access control triad, stating what values vary. What other values could vary? Use this to suggest new useful roles for those systems.

21) How can roles, by definition, vary? For three different social technical systems, describe how each role variation type might work. Give three different examples of implemented roles and suggest three future developments.

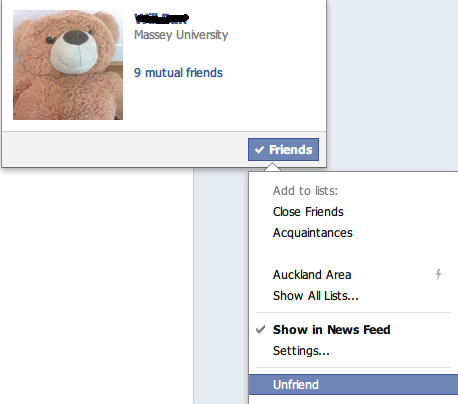

22) If you unfriend a person, should they be informed? Test and report what actually happens on three common social networks. Must a banned bulletin board “flamer” be notified? What about someone kicked out of a chat room? What is the general principle here?

23) What is a meta-right? Give physical and online examples. How does it differ from other rights? Is it still a right? Can an access control system act on meta-rights? Are there meta-meta-rights? If not, why not? What then does it mean to “own” an entity?

24) Why can creating an item not be an act on that item? Why can it not be an act on nothing? What then is it an act upon? Illustrate with online examples.

25) Who owns a newly created information entity? By what social principle? Must this always be so? Find online cases where you create a thing online but do not fully own it.

26) In a space, who, initially, has the right to create in it? How can others create in that space? What are creation conditions? What is their justification?

27) Find online examples of creation conditions that limit the object type, operations allowed, access, visibility and restrict edit rights. How obvious are the conditions to those creating the objects?

28) Give three examples of creating an entity in a space. For each, specify the owner, parent, ancestors, offspring and local public. Which role(s) can the owner change?

29) For five different social technical systems genres, demonstrate online creation conditions by creating something in each. How obvious were the creation conditions? Find examples of non-obvious conditions.

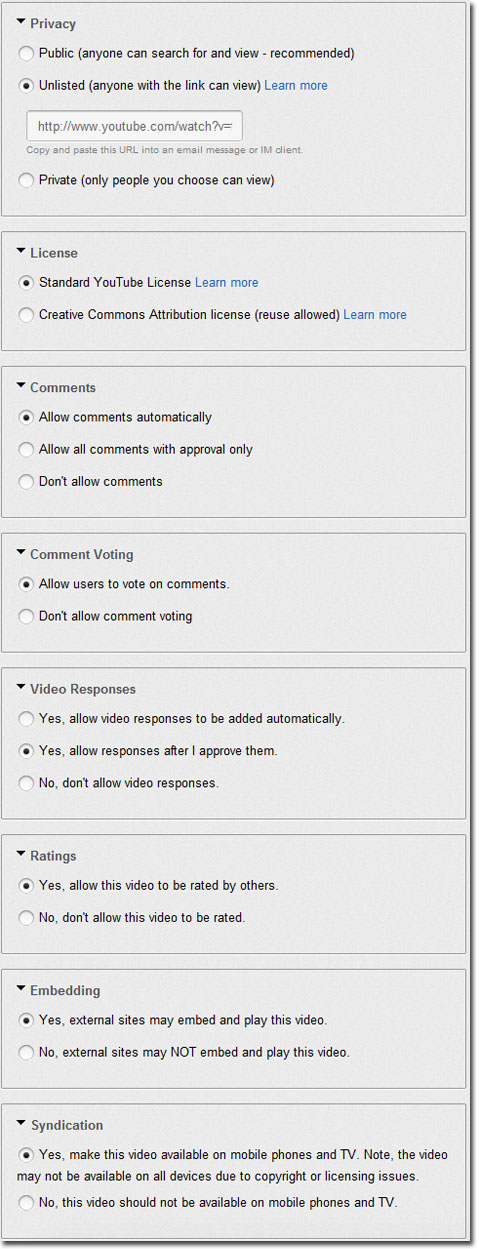

30) For the following, explain why or why not. Suppose you are the chair of a computer conference with several tracks. Should a track chair be able to exclude you, or hide a paper from your view? Should you be able to delete a paper from their track? What about their seeing papers in other tracks? Should a track chair be able to move a paper submitted to their track by error to another track? Investigate and report comments you find on online systems that manage academic conferences.

31) An online community has put an issue to a member vote. Discuss the social effect of these options:

a) Voters can see how others voted, by name, before they vote.

b) Voters can see the vote average before they vote.

c) Voters can only see the vote average after they vote, but before all voting is over.

d) Voters can only see the vote average after all the voting is over.

32) An online community has put an issue to a member vote. Discuss the effect of these options:

a) Voters are not registered, so one person can vote many times.

b) Voters are registered, but can change their one vote any time.

c) Voters are registered, and can only vote once, with no edits.

Which option might you use and when?

33) Can the person calling a vote legitimately define vote conditions? What happens if they set conditions such as that all votes must be signed and will be made public?

34) Is posting a video online like posting a notice in a local shop window? Explain, covering permission to post, to display, to withdraw and to delete. Can a post be deleted? Can it be rejected? Explain the difference. Give online examples.

35) Give physical and online examples of rights re-allocations based on rights and meta-rights. If four authors publish a paper online, list the ownership options. Discuss how each might work out in practice. Which would you prefer and why?

36) Should delegating give the right to delegate? Explain, with physical and online examples. What happens to ownership and accountability if delegatees can delegate? Discuss a worst case scenario.

37) If a property is left to you in a will, can you refuse to own it, or is it automatically yours? What rights cannot be allocated without consent? What can? Which of these rights can be freely allocated: Paper author. Paper co-author. Track chair. Being friended. Being banned. Bulletin board member. Logon ID. Bulletin board moderator. Online Christmas card access? Which rights allocations require receiver consent?

38) Investigate how social network connections multiply. For you and five others find out the number of online friends and calculate the average. Based on this, estimate the average friends of friends in general. Estimate the messages, mails, notifications etc. you get from all your friends per week, and from that calculate an average per friend per day. If you friended all your friend’s friends, potentially, how many messages could you expect per day? What if you friended your friend’s friend’s friends too? Why is the number so large? Discuss the claim of the film Six Degrees of Separation, that everyone in the world is just six links away from everyone else.

39) Demonstrate how to “unfriend” a person in three social networks. Are they notified? Is unfriending “breaking up”? That an “anti-friend” is an enemy, suggests “anti-Facebook” sites. Investigate technology support for people you hate, e.g. celebrities or my relationship ex. Try anti-organization sites, like sickfacebook.com. What purpose could technology support for anti-friendship serve?