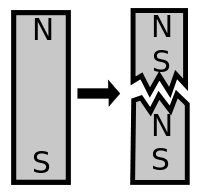

Magnetism differs from charge because splitting a magnet gives two more magnets, each with its own north and south pole (Figure 5.13), but dividing a polar charge gives positive and negative parts. And joining two small magnets gives a big one so if big magnets come from small ones, all magnetism comes from the smallest possible magnet, which is the electron.

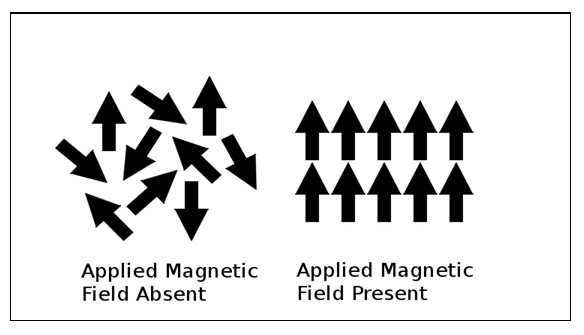

Electrons explain why metals can be magnets but not plastics. Copper can conduct electricity because its electrons move freely, and it becomes a magnet for the same reason. The electrons in a metal usually point randomly but if they all point the same way, it becomes a magnet (Figure 5.14). In contrast, the electrons in plastics can’t move freely, so plastic can’t conduct electricity or become magnetic. Electrons then explain electricity and magnetism.

In physics, an electron is essentially a tiny magnet, whose north pole is at right angles to its spin, and whose south pole is the opposite, so could spin cause magnetism?

Quantum theory requires all matter to spin, so it is a basic property of matter, like mass and charge. It is thought to be imaginary because an electron as a point particle can’t spin but, in this model, electrons actually do spin in quantum space.

If spin causes magnetism, north and south poles are directions not parts, so spin always has both just as a plate always has both top and bottom sides. Splitting a magnet then always gives two magnets because separated spins still have two sides. In this analogy, mass and charge, like the weight and color of a plate, can be split, but north and south poles, like the top and bottom of a plate, can’t be split. It follows that a north pole can’t exist without a south pole, and the evidence agrees.

In contrast, particle models allow the possibility of magnetic monopoles, elementary particles with one magnetic pole. Nothing in Maxwell’s equations of magnetism prohibits them, so despite no evidence, they are argued to exist (Rajantie, 2016). But if spin causes magnetic poles, monopoles can’t exist, so they are just another fruitless search, like that for gravitons.

What then does spin do? By the Pauli exclusion principle, opposite-spin electrons can occupy the same point but same-spin electrons can’t. The reason given here is that electrons can spin into different regions of quantum space (4.7.1), so if one spins up and the other down, they don’t overlap, while same-spin electrons compete for the same space. Opposite spin electrons can then occupy the same point but same spin electrons can’t.

If quantum processing spreads, the distribution around a magnet includes its spin. It doesn’t affect gravity much but between magnets, spin has an effect. Between opposite magnets, opposite spins make more space available, so the quantum field deepens, but between same magnets, same-spins compete for the same space, by the Pauli principle, so the quantum field is shallower.

Magnets then bias the quantum field between them as charges do. Between opposite magnets, the deeper field lets processing overlap with less competition, so it is faster. The magnets then restart more often where the field is faster, so they move together, i.e. attract. But between same magnets, same-spins compete for the same space, so it runs slower. The magnets then restart more often away from each other, so they move apart, i.e. repel. It follows that magnets attract or repel by biasing the speed of the quantum field between them as charge does, but for a different reason.

Gravity, charge, and magnetism then move matter in the same way, by biasing the quantum field around it. Gravity biases the field strength around other matter to attract it only. Charges and magnets move each other by biasing the speed of the field between them, to attract or repel. In all cases, matter moves when the field around it makes it tremble more often one way.

If charge and magnetism both involve electrons, why don’t static charges affect magnets? If magnetism is based on spin, and charge is a processing remainder, these properties won’t interact. Spin doesn’t change charge, and charge doesn’t change spin, so they don’t affect each other.

This model also explains why charge and magnetism act at right angles. Electric fields act to move electrons in one direction as a current, but electrons as one-dimensional matter must align their matter axes to do this. If their spin is magnetism, it then acts at right angles to the current direction because an electron’s spin is always at right angles to its matter axis.

Currents then cause magnetism because aligning an electron’s axis to move it also sets its spin, so electrons going one way spin one way, and going the other way spin the opposite. Equally, when a magnet moves, it acts to align the electron’s axes, so they move as a current.

Magnetism based on spin also suggests why it fades faster than charge. Charge decreases as an inverse square because it spreads on a two-dimensional sphere surface, but spin deepens space, so magnetism also spreads in another dimension. The effect is less between same poles, but it explains why magnetism decreases more as an inverse cube than an inverse square.

In this model, gravity, charge, and magnetism move objects by biasing different aspects of the same quantum field, where gravity biases its strength, and magnetism and charge both bias its speed. Gravity, charge, and magnetism then act at a distance, with no need for particles at all.