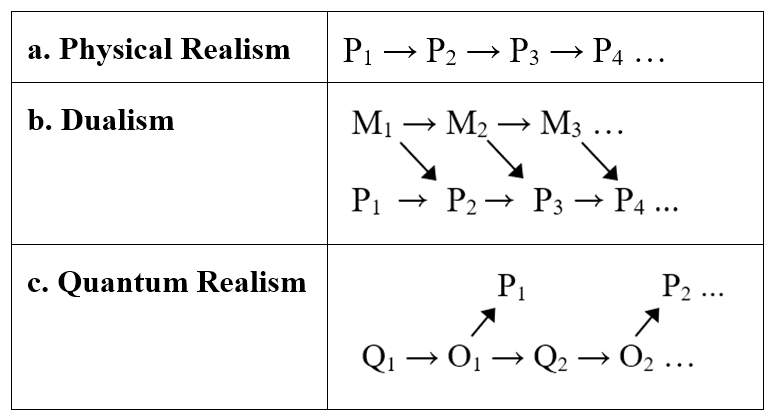

Chalmer’s last option is neutral monism, that something more primal than matter or mind is the cause of both, as suggested by Russell in 1921:

“The stuff of which the world of our experience is composed is, in my belief, neither mind nor matter, but something more primitive than either. Both mind and matter seem to be composite, and the stuff of which they are compounded lies in a sense between the two, in a sense above them both, like a common ancestor.” (Russell, 2005)

Russell didn’t specify a common ancestor for mind and matter, but if quantum reality creates the observer as well as physical events, quantum realism is a neutral monism as Russell proposed.

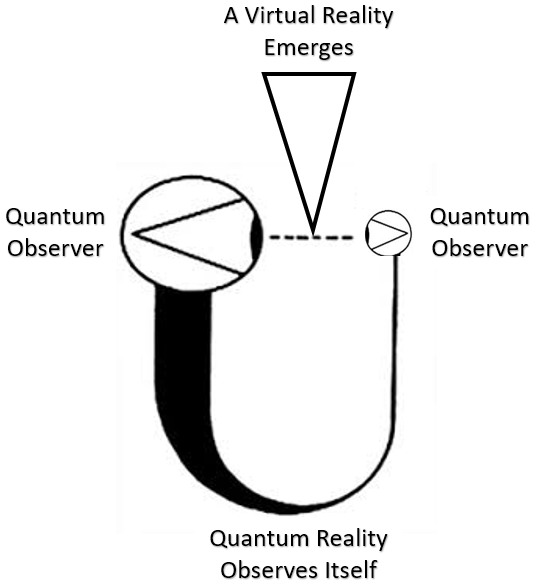

Consider the premise that every physical event must have an observer. Virtual worlds exist by being observed so if our physical reality is virtual, it should be the same. Quantum theory confirms that physical events require observation, as spreading quantum waves only collapse to a physical event when observed. It follows that an observer is needed for physical events to occur.

We also know that our universe began at a moment in time so without observation, it would have stayed in a quantum superposition. The initial physical events had to be observed to occur. If our universe began as a light plasma that physically collided into basic matter (Chapter 3), the only entities that could observe were photons. The simplest conclusion that lets observation cause the initial physical events is that photons observed.

It isn’t claimed that photons observe as we do, but that they observe quantum scale events of 10-35 meters and 10-43 seconds. Such events are incredibly short and brief to us, as they occur more times per second than there have been seconds in our universe. That photons observe seems preposterous but the alternative, that only we observe the universe, is equally so.

To observe so little so briefly seems hardly worth it to us, but smallism, that facts about big things come from facts about small things (Coleman, 2006), can apply to observation too. If the observer experience began small, like everything else, then macro-consciousness can derive from micro-consciousness (Chalmers, 1996) (p305). It is possible that photons observe, so who are we to say that they don’t when we claim that we do? By Conway’s free will theorem, either everything is conscious or nothing is (Koch, 2014), so it is simpler to say that observation always existed than to explain how it began with no precedent.

If observation existed from the start, then photons observe on their scale, but not as we do. To avoid confusion, let us call quantum-scale observations proto-consciousness, as Penrose proposed in 1944 (Penrose, 1994), and more recently:

“… the elements of proto-consciousness would be intimately tied in with the most primitive Planck level ingredients of space-time geometry, these presumed ‘ingredients’ being taken to be at the absurdly tiny level of 10-35m and 10-43s, a distance and time some 20 orders of magnitude smaller than those of normal particle-physics scales and their most rapid processes.” (Penrose & Hameroff, 2017) p21.

That consciousness began small answers another question, that if everything is a player in our virtual universe, isn’t it boring for some? If one asked for players in a virtual universe like ours, who wants to be a rock on mars, that just sits there for a million years? But a rock is an aggregate of molecules, so it observes on a molecular scale, not a rock scale. On this scale, something new happens every nanosecond, so it isn’t boring at all.

This isn’t panpsychism, that matter is conscious, because in quantum realism, matter doesn’t exist except as a view. Panpsychism assumes that matter exists to have a consciousness property, but if matter itself doesn’t exist, it can’t have that property. This is possible because previous chapters derived matter properties, like mass, charge, and spin, from quantum reality.

Quantum realism changes the question from how dead matter became able to observe to how proto-observations became human observations. It replaces the explanatory gap between matter and consciousness with an evolutionary gap, between what atoms observe and what we do. The conclusion, developed later, is that the ability to observe had to exist from the beginning to cause physical events. Hence, instead of asking how matter acquired consciousness, we now ask how matter observations evolved, which raises the question of how brains evolved?