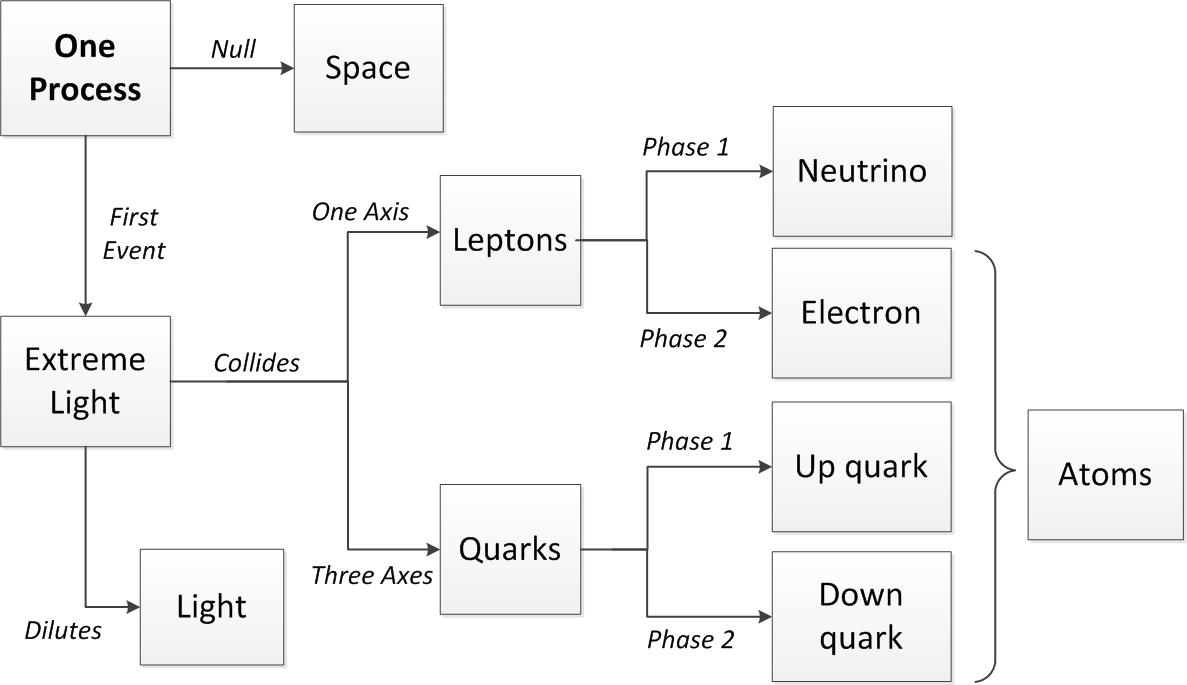

The model of Figure 4.19 is based on one process, a simple circle that gives the null result of space. A first event then separated this process to begin our universe as a plasma of pure light, with no matter at all. This extreme light was diluted by the expansion of space, but some collided to make the first matter. A one-axis collision gave electrons or neutrinos based on phase, while a three-axis collision gave up or down quarks also based on phase. In both cases, the net processing that repeated was mass and what didn’t run was charge.

Quarks then combined into protons or neutrons by sharing photons to give nuclei that attracted electrons. The first atom, Hydrogen, was just a proton and an electron, but neutrons allowed higher atoms to form by nucleosynthesis. Space, light, and matter then all come from the same quantum process.

Unlike the standard particle model (Figure 4.18), this model (Figure 4.19) explains:

1. The origin of matter. Matter evolved, first from light, then into higher atoms, so it isn’t fundamental.

2. The forces of nature. All forces come from quantum waves on a network, not particle agents.

3. Anti-matter. Processing implies anti-processing, while particles have no natural inverse.

4. Space. Space is a network null process, not nothing at all.

5. Neutrinos. The neutrino is an electron byproduct, not a pointless particle.

6. Charge. Charge is a mass byproduct, not an arbitrary property.

7. Quarks. Quarks are a three-way electron collision.

The model of Figure 4.19 has no virtual agents and the same process underlies light, matter, and space. It also answers questions that a particle model can’t, such as:

1. Why does matter have mass and charge? (4.3.2)

2. Why do neutrinos have a tiny but variable mass? (4.3.3)

3. Why does anti-matter exist? (4.3.4)

4. Why isn’t anti-matter around today? (4.3.5)

5. Why are quark charges in strange thirds? (4.4.3)

6. Why does the nuclear force increase with distance? (4.4.4)

7. Why don’t protons decay in empty space? (4.4.6)

8. Why does the energy of matter depend on the speed of light? (4.4.8)

9. Why do atomic nuclei need neutrons? (4.6.1)

10. How did electron shells evolve? (4.6.2)

11. Why do charges add simply but mass doesn’t? (4.7.3)

12. Why is the universe charge neutral? (4.7.4)

13. What is dark matter? (4.7.6)

14. What is dark energy? (4.7.7)

These answers require only that quantum theory describes processing waves spreading on a network. The quantum network defines space and keeps point entities apart naturally, and a network transfer rate of one point per cycle makes the speed of light constant. Electrons and neutrinos are then brother leptons as they are phases of the same interaction, and up and down quarks as phases of a three-axis interaction will have one-third charges. Finally, a process that creates matter allows an anti-process to create anti-matter. One process that evolved can explain what many particles can’t.

The idea that God made our world like a clock, from existing parts, doesn’t work. If the particles of the standard model are a universal Lego-set, why are higher electrons and quarks irrelevant to the world we see? And if these bits were lying around before our universe began, where did they come from?

The simpler alternative is that before our universe began, it didn’t exist at all, so instead of divine shortcuts, everything had to be made, including our space and time! This wasn’t possible in one step so light, being simpler, began before matter did.

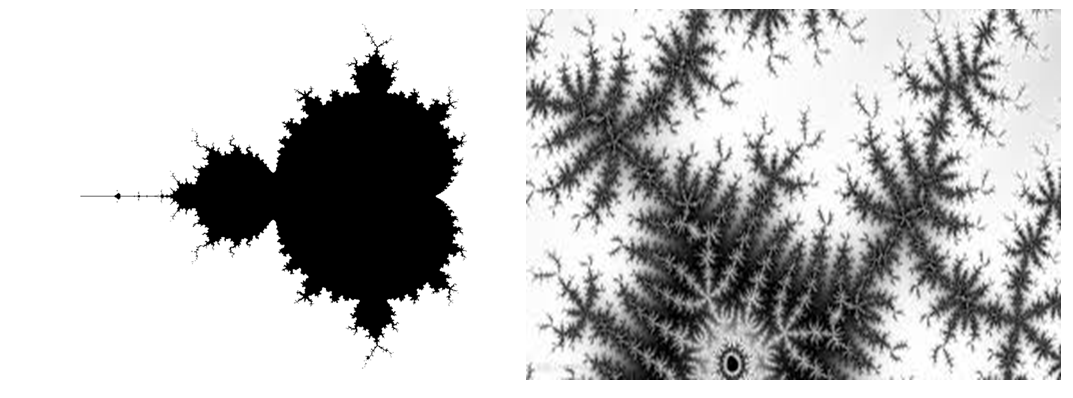

The Mandelbrot set illustrates how one process can evolve complexity, as one line of code repeated produces an endless variety of outcomes (Figure 4.20).

And if space became light that became matter that became us, our entire universe could have come from what we call nothing:

“The world is a thing of utter inordinate complexity and richness and strangeness that is absolutely awesome. I mean the idea that such complexity can arise not only out of such simplicity, but probably absolutely out of nothing, is the most fabulous extraordinary idea. And once you get some kind of inkling of how that might have happened, it’s just wonderful.” Douglas Adams, quoted by Dawkins in his eulogy for Adams (17 September, 2001).

That physical complexity comes from quantum simplicity supports Adam’s vision, but how can this theory be tested?